Isolated Hepatic Mucormycosis in the Early Post-Transplant Period: A Case Report and Literature Review

Michael Czapka 1,*![]() , Carlos A.Q. Santos 2

, Carlos A.Q. Santos 2![]() , Laurie A. Proia 2

, Laurie A. Proia 2![]()

- Division of Internal Medicine, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA

- Division of Infectious Disease, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA

* Correspondence: Michael Czapka ![]()

Academic Editor: Maricar Malinis

Special Issue: Diagnosis and Management of Infections in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients

Received: October 8, 2018 | Accepted: January 29, 2019 | Published: February 1, 2019

OBM Transplantation 2019, Volume 3, Issue 1 doi:10.21926/obm.transplant.1901045

Recommended citation: Czapka M, Santos CAQ, Proia LA. Isolated Hepatic Mucormycosis in the Early Post-Transplant Period: A Case Report and Literature Review. OBM Transplantation 2019; 3(1): 045; doi:10.21926/obm.transplant.1901045.

© 2019 by the authors. This is an open access article distributed under the conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is correctly cited.

Abstract

Mucormycosis is a rare fungal infection associated with high morbidity and mortality that typically afflicts immunocompromised hosts. We present a case of isolated hepatic mucormycosis with Rhizopus spp. that developed in the early post-transplant period. Initial presentation was concerning for allograft rejection, but definitive diagnosis was made with histopathology and fungal culture. The patient had a favourable outcome with surgical resection, a course of liposomal amphotericin B combined with micafungin, and chronic suppressive therapy with posaconazole. We encountered only four cases of isolated hepatic mucormycosis in solid organ transplant recipients in the literature that presented as either fungal abscess or surgical anastomosis rupture. This case report and literature review demonstrates the need for urgent diagnosis and management of this uncommon condition and outlines an effective therapeutic regimen.

Keywords

Mucor; mucormycosis; rhizopus; hepatic; solid organ transplant; liver; posaconazole

1. Introduction

Mucormycosis is a rare, angioinvasive infection caused by fungi predominantly within the order Mucorales [1]. These organisms are ubiquitous in the natural environment, and exposure occurs through inhalation or ingestion of spores, or less commonly, through inoculation by penetrating trauma [2]. Sino-orbital, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and cutaneous sites are most commonly infected. Persons who develop infection are often immunocompromised from neutropenia, uncontrolled diabetes, hematologic malignancy, transplantation, or are iron overloaded [3,4]. Mortality from mucormycosis is high, and estimated to be 23% in a recent analysis [5]. Treatment typically includes surgical resection (proven to be of benefit in sinopulmonary disease) [6], and anti-fungal therapy with amphotericin [7]. More recently, the triazoles isavuconazole and posaconazole have been used as alternative or salvage therapy [8,9]. Herein we present a case of isolated hepatic mucormycosis developing less than four weeks after orthotopic liver transplant which was successfully treated with liposomal amphotericin B, multiple surgical resections, and chronic suppressive therapy with posaconazole.

2. Case Report

A 53-year-old man with a history of decompensated cirrhosis (complicated by portal hypertension, esophageal varices, and ascites) secondary to alpha-1-anti-trypsin deficiency, well controlled diabetes mellitus and hypertension was transferred to our institution from an outside hospital for suspected gastroparesis. The patient was already listed for liver transplant at the time of admission. Notably, admission studies revealed moderate neutropenia, with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 600/µl.

On day two of admission, a donor liver became available, and patient underwent orthotopic liver transplantation without any immediate complications. The patient’s ANC rose to 22 K/µl following surgery. A donor core needle liver biopsy showed no evidence of fibrosis, or any other underlying pathology. The patient received 500 mg of methylprednisolone intra-operatively, followed by gradual taper over three days. Mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus were initiated on post-operative day one. Pathology from the explanted liver showed cirrhosis with numerous PAS-D positive intracytoplasmic globules consistent with alpha-1-anti-trypsin deficiency, a scattered moderate increase in hepatocellular iron (grade 2 of 4), no stainable copper, patchy mild macro vesicular steatosis, and increased hepatocellular nuclear glycogen that was probably related to diabetes. There were no signs of fungal infection.

On post-operative day six, serum bilirubin up-trended as transaminases down-trended, and an ultrasound and liver biopsy were obtained. Abdominal sonogram was normal, but core needle biopsy demonstrated severe cholestasis and severe acute cholangiolitis interpreted as likely secondary to biliary obstruction. Given concerns for stricture, an ERCP was performed which showed an anastomotic stricture in the common bile duct necessitating stent placement. The patient was discharged to an on-site acute rehabilitation facility on post-operative day 14 with continued follow up by transplant surgery and hepatology teams.

On post-operative day 16, the patient developed worsening liver function tests: total bilirubin increased from 2.8 to 4.2 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase decreased from 93 to 58, aspartate transaminase (AST) rose from 34 to 174 U/L, and alanine transaminase (ALT) rose from 61 to 204 U/L. No neutropenia was present at that time. Given concerns for allograft rejection, mycophenolate dosing was increased to 500 mg every 12 hours, and the patient was given methylprednisolone 500 mg IV daily for five days. A right upper quadrant ultrasound was performed and showed an ovoid, heterogeneous, avascular, subcapsular structure along the hepatic dome. This was initially interpreted to be a resolving postoperative hematoma. However, the patient developed right sided abdominal pain, and underwent repeat abdominal ultrasonography which showed a slight increase in size of the heterogenous lesion in the hepatic dome, and more liquefied components extending into the adjacent perihepatic space. A triple-phase contrast computed tomography scan of abdomen and pelvis confirmed the presence of a large multi-loculated fluid density lesion within the right hepatic lobe with peripheral enhancement and internal septal enhancement that was interpreted to be most concerning for abscess.

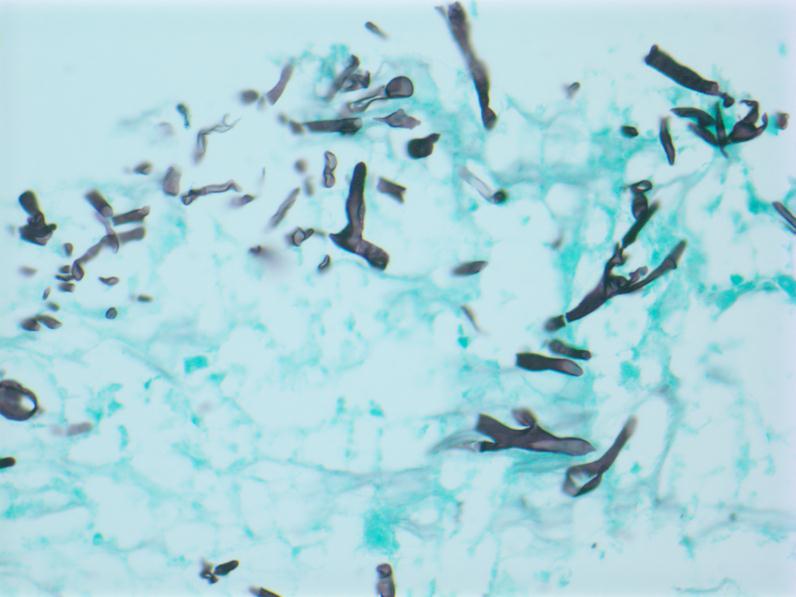

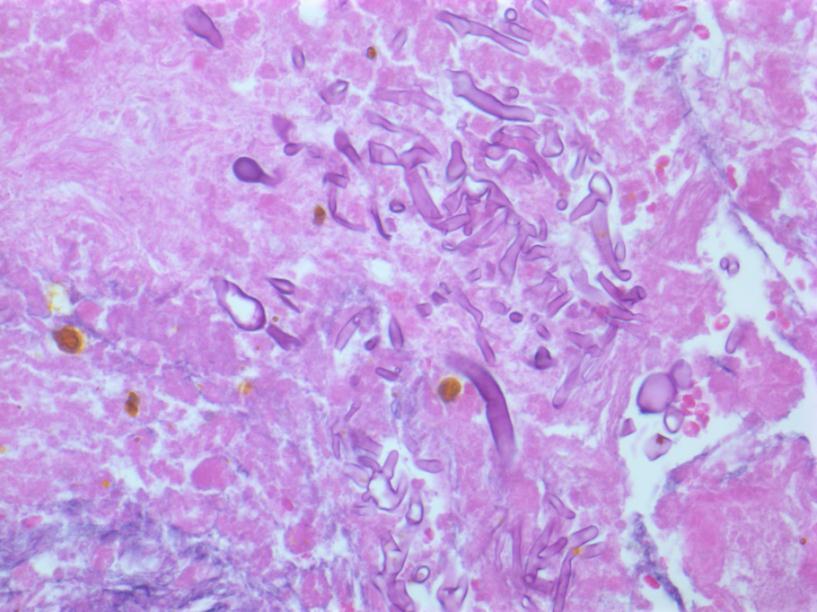

Given imaging findings concerning for liver abscess, interventional radiology performed an ultrasound guided aspiration of the hepatic fluid collection on post-operative day 25. Vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam were also initiated. Fungal smear from aspirated fluid revealed non-septate hyphae, suggestive of a mucorales mould. High dose liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg IV daily) and micafungin 150 mg IV daily were initiated. The patient was taken emergently for exploratory laparotomy, and debridement of the liver abscess. Following this procedure, the remaining cavity was irrigated with a solution comprised of 50 mg of amphotericin B deoxycholate in 1000 mL of sterile water. Irrigation of the abscess space every four hours was continued via Jackson-Pratt drains. Histopathology of the abscess wall showed severely inflamed granulation tissue, reactive cholangiolar proliferation, reactive inflammatory giant cells and numerous hyphal structures consistent with mucormycosis (Figures 1, 2). Fungal cultures from operative specimens grew Rhizopus spp -our laboratory did not perform speciation or susceptibility testing. At time of diagnosis and in the admission preceding this incident, the patient did not endorse sinopulmonary symptoms. Imaging of the chest and sinuses showed no findings concerning for invasive fungal infection. Over the following weeks, the patient underwent repeated surgical debridements of the liver until the margins were clear of disease. Pathologic specimens during this time were also noted to have tissue invasive CMV, and the patient was treated with a 14-day course of IV ganciclovir followed by a three-month course of oral valganciclovir.

The patient was treated with liposomal amphotericin B and micafungin for six weeks for the Rhizopus infection and transitioned to monotherapy with oral delayed-release posaconazole tablets (300 mg Q12 hours on day 1, then 300 mg once daily from day 2 onwards). The most recent computed tomography scan of the patient’s abdomen and pelvis two years following diagnosis of hepatic mucormycosis showed no evidence of liver lesions. He has done well on follow-up and continues to be on posaconazole therapy.

Figure 1 Hepatocytes with adjacent fungal hyphae consistent with mucormycosis. Grocott’s methenamine silver stain, 200x magnification.

Figure 2 Hepatocytes with adjacent fungal hyphae consistent with mucormycosis. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 400x magnification.

3. Discussion

We found seventeen cases of isolated hepatic mucormycosis in the literature [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], of which the majority had hematologic malignancy with associated neutropenia and/or cytotoxic chemotherapy. We identified only four cases of isolated hepatic mucormycosis in solid organ transplant recipients, of whom three had liver transplants and one had a kidney transplant (Table 1). The small number of cases makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions, but it appears that isolated hepatic mucormycosis presents as either fungal abscess formation (as with our patient) or vascular invasion causing rupture of surgical anastomoses. Diagnosis is attained through microbiological and histopathological methods, and management includes surgical and medical therapy. Surgical resection of disease combined with medical therapy has previously been demonstrated to improve outcomes when compared to anti-fungals alone [28]. Regarding medical therapy, available agents with activity against Mucorales include amphotericin, posaconazole and isavuconazole [29]. Amphotericin is the best studied of the above anti-fungals, and remains the preferred initial therapy for mucormycosis, with treatment usually lasting for at least six weeks (although tailoring of therapy to individual circumstance and response is common) [30]. Posaconazole may be used as salvage or suppressive therapy against mucormycosis [31]. Isavuconazole has been found to have comparable outcomes to amphotericin in a compassionate use trial [9]. While echinocandins have not demonstrated effectiveness against Mucorales on their own, a murine study and a small human trial have shown improved outcomes when an echinocandin was used in combination with amphotericin, suggesting potential synergy [32,33]. A larger study subsequently demonstrated no difference in outcomes with echinocandin and polyene combination therapy [34], suggesting that adding an echinocandin to a polyene-based regimen should be made on a case by case basis. As immunosuppression in organ transplant recipients can never be fully lifted, the question of duration of suppressive anti-fungal therapy for Mucorales infections in this sub-set of patients remains open. The rarity of this infection, and therefore the paucity of data, makes this question difficult to study. Given the severity of initial infection with repeated debridements of the allograft, we have elected to keep our patient on posaconazole therapy indefinitely.

One of the more curious aspects of our case, and other similar cases, was the isolated hepatic involvement of infection. Typically, infection begins with inhalation of spores into the nares, oropharynx or airways, or with ingestion of spores in cases of gastrointestinal mucormycosis. However, in our patient along with other similar cases in Table 1, there was no evidence of other organ involvement. In the case of Abboud et al., the authors surmised the source was possibly donor derived as the liver donor was a prior kidney transplant recipient on immunosuppression [22]. Mekeel et al. were unable to find an obvious source for the infection as the transplanted kidney did not have evidence of mucormycosis on pathology [16]. Del Pont et al demonstrated evidence of Mucorales infection within the external surgical site, leading to the thought that the wound was contaminated by adhesive bandages or airborne spores that led to a deeper infection [15]. Zhan et al. also believe the source involved the donor graft, in either a pre-existing infection of the tissue or environmental contamination during prolonged harvest, transportation, and surgical time [17]. Regarding our patient, we reviewed records of other organ recipients from our case’s liver donor, and did not find other cases of mucormycosis, making a donor-derived infection less likely. Peri-operative contamination or seeding from bandages remain possibilities in keeping with the other cases of isolated hepatic mucormycosis listed above.

This case adds to the small but growing literature of hepatic mucormycosis following orthotopic liver transplant and details an effective strategy for treatment that includes medical therapy and aggressive surgical debridement. Although rare, hepatic mucormycosis can be associated with high morbidity and mortality in liver transplant recipients and should be considered in patients with liver abscess formation or rupture of surgical anastomoses.

Table 1 Cases of hepatic mucormycosis in solid organ transplant recipients.

Acknowledgments

Shriram M. Jakate, MD, for interpretation and supply of pathology images.

Author Contributions

Laurie Proia: Managed case, edited paper; Michael Czapka: wrote initial draft, performed literature review, edited paper; Carlos Santos: edited paper, performed additional literature search.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Kwon-Chung KJ. Taxonomy of fungi causing mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis (zygomycosis) and nomenclature of the disease: Molecular mycologic perspectives. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 54: S8-S15. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000; 13: 236-301. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: A review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 41: 634-653. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim AS. Host-iron assimilation: Pathogenesis and novel therapies of mucormycosis. Mycoses. 2014; 57: 13-17. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Kontoyiannis DP, Yang H, Song J, Kelkar SS, Yang X, Azie N, et al. Prevalence, clinical and economic burden of mucormycosis-related hospitalizations in the United States: A retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016; 16: 730. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Tedder M, Spratt JA, Anstadt MP, Hegde SS, Tedder SD, Lowe JE. Pulmonary mucormycosis: Results of medical and surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994; 57: 1044-1050. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Gleissner B, Schilling A, Anagnostopolous I, Siehl I, Thiel E. Improved outcome of zygomycosis in patients with hematological diseases? Leuk Lymphoma. 2004; 45: 1351-1360. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Enoch DA, Aliyu SH, Sule O, Lewis SJ, Karas JA. Posaconazole for the treatment of mucormycosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011; 38: 465-473. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Marty FM, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Cornely OA, Mullane KM, Perfect JR, Thompson GR, et al. Isavuconazole treatment for mucormycosis: A single-arm open-label trial and case-control analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016; 16: 828-837. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Asiri RH, Van Dijken PJ, Mahmood MA, Al-Shahed MS, Rossi ML, Osoba AO. Isolated hepatic mucormycosis in an immunocompetent child. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996; 91: 606-607. [Google scholar]

- Erdem G, Cağlar M, Ceyhan M, Akçören Z, Kanra G. Hepatic mucormycosis in a child with fulminant hepatic failure. Turk J Pediatr. 1996; 38: 511-514. [Google scholar]

- Oliver MR, Van Voorhis WC, Boeckh M, Mattson D, Bowden RA. Hepatic mucormycosis in a bone marrow transplant recipient who ingested naturopathic medicine. Clin Infect Dis. 1996; 22: 521-524. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsaousis G, Koutsouri A, Gatsiou C, Paniara O, Peppas C, Chalevelakis G. Liver and brain mucormycosis in a diabetic patient type II successfully treated with liposomial amphotericin B. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000; 32: 335-337. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Suh IW, Park CS, Lee MS, Lee JH, Chang MS, Woo JH, et al. Hepatic and small bowel mucormycosis after chemotherapy in a patient with acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Korean Med Sci. 2000; 15: 351-354. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Del Pont JM, De Cicco L, Gallo G, Llera J, De Santibanez E, D’Agostino D. Hepatic arterial thrombosis due to mucor species in a child following orthotopic liver transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2000; 2: 33-35. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Mekeel KL, Hemming AW, Reed AI, Matsumoto T, Fujita S, Schain DC, et al. Hepatic mucormycosis in a renal transplant recipient. Transplantation. 2005; 79: 1636. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhan HX, Lv Y, Zhang Y, Liu C, Wang B, Jiang YY, et al. Hepatic and renal artery rupture due to aspergillus and mucor mixed infection after combined liver and kidney transplantation: A case report. Transplant Proc. 2008; 40: 1771-1773. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Lüer S, Berger S, Diepold M, Duppenthaler A, von Gunten M, Mühlethaler K, et al. Treatment of intestinal and hepatic mucormycosis in an immunocompromised child. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009; 52: 872-874. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Li K, Wen T, Li G. Hepatic mucormycosis mimicking hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2010; 16: 1039-1042. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Sickels N, Hoffman J, Stuke L, Kempe K. Survival of a patient with trauma-induced mucormycosis using an aggressive surgical and medical approach. J Trauma. 2011; 70: 507-509. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Su H, Thompson GR, Cohen SH. Hepatic mucormycosis with abscess formation. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012; 73: 192-194. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Abboud CS, Bergamasco MD, Baía CES, et al. Case report of hepatic mucormycosis after liver transplantation: Successful treatment with liposomal amphotericin B followed by posaconazole sequential therapy. Transplant Proc. 2012; 44: 2501-2502. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan A, Kumaran V, Jain D, Siraj F, Aggarwal S. Hepatic mucormycosis in a patient of acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A case report with literature review. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2013; 29: 96-98. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Tuysuz G, Ozdemir N, Senyuz OF, et al. Successful management of hepatic mucormycosis in an acute lymphoblastic leukaemia patient: A case report and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2014; 57: 513-518. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang C, Friess SH, Dehner LP. Hepatic mucormycosis mimicking veno-occlusive disease: Report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2016; 19: 150-153. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernardo RM, Gurung A, Jain D, Malinis MF. Therapeutic challenges of hepatic mucormycosis in hematologic malignancy: A case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2016; 17: 484-489. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Vikum D, Nordoy I, Torp Andersen C, Fevang B, Line PD, Kolrud FK, et al. A young, immunocompetent woman with small bowel and hepatic mucormycosis successfully treated with aggressive surgical debridements and antifungal therapy. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2017; 2017: 4173246. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Almyroudis NG, Sutton DA, Linden P, Rinaldi MG, Fung J, Kusne S. Zygomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients in a tertiary transplant center and review of the literature. Am J Transplant. 2006; 6: 2365-2374. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Danion F, Aguilar C, Catherinot E, Alanio A, DeWolf S, Lortholary O, et al. Mucormycosis: New developments into a persistently devastating infection. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 36: 692-705. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Skiada A, Lanternier F, Groll AH, Pagano L, Zimmerli S, Herbrecht R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of mucormycosis in patients with hematological malignancies: Guidelines from the 3rd european conference on infections in leukemia (ECIL 3). Haematologica. 2013; 98: 492-504. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Cornely OA, Arikan-Akdagli S, Dannaoui E, Groll AH, Lagrou K, Chakrabarti A, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis 2013. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014; 20: 5-26. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim AS, Gebremariam T, Fu Y, Edwards JE, Spellberg B. Combination echinocandin-polyene treatment of murine mucormycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008; 52: 1556-1558. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Reed C, Bryant R, Ibrahim AS, Edwards J, Filler SG, Goldberg R, et al. Combination polyene-caspofungin treatment of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 47: 364-371. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Kyvernitakis A, Torres HA, Jiang Y, Chamilos G, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Initial use of combination treatment does not impact survival of 106 patients with haematologic malignancies and mucormycosis: A propensity score analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016; 22: 811. e1-811. e8. [Google scholar]