A Call to Arms for the Aged Care Sector: A Spotlight on Systematic Abuse and Neglect of Older Disabled Persons

Terence Seedsman 1, * ![]() , Nilufer Korkmaz-Yaylagul 2

, Nilufer Korkmaz-Yaylagul 2 ![]()

- College of Sport and Exercise Science, Victoria University, PO Box 14428, Melbourne, Vic 8001, Australia

- Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Gerontology, Akdeniz University, Antalya, Turkey

* Correspondence: Terence Seedsman ![]()

Academic Editor: Lisa A. Hollis-Sawyer

Special Issue: Got Aging? Examining Later-life Development from a Positive Aging Perspective

Received: July 17, 2018 | Accepted: November 12, 2018 | Published: November 28, 2018

OBM Geriatrics 2018, Volume 2, Issue 4 doi:10.21926/obm.geriatr.1804022

Recommended citation: Seedsman T, Korkmaz-Yaylagul N. A Call to Arms for the Aged Care Sector: A Spotlight on Systematic Abuse and Neglect of Older Disabled Persons. OBM Geriatrics 2018;2(4):022; doi:10.21926/obm.geriatr.1804022.

© 2018 by the authors. This is an open access article distributed under the conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is correctly cited.

Abstract

With rapidly aging populations worldwide there will be an increasing need to focus attention on the expected increase in disability with advancing age. Drawing upon established literature this paper aims to highlight the contribution of anthropology including selected research findings and contemporary understandings surrounding ageism, abuse and exploitation of older disabled persons. Health care providers within the context of the aged care sector are challenged to unburden themselves with negative images and practices surrounding aging and disability. Quality of life is seen as a fundamental and indisputable goal of the aged care sector that incorporates a focus on wellness, active aging and respect for the diversity among disabled older persons including the importance of helping each individual to achieve a good old age. A life course approach is offered for understanding disability including social system failures known to arise from the influence of discrimination and ageism. Disability is portrayed as first residing in the individual with disability while also representing a major public health challenge. Evidence shows that effective programming for disability prevention can lower the incidence of disability in later life. At the same time, it is shown that there are people with lifelong disabilities that are non-modifiable in comparison to a host of modifiable lifestyle risk factors. It is also demonstrated that people who are aging with disabilities do not represent a uniform group. The contemporary concept of ‘successful aging’ is challenged on the basis that it can be seen as being discriminatory to older people with disabilities. Societies claiming to have humanitarian concerns for the aged are challenged to demonstrate that they have in place responsive policies and integrated health care service systems that can prevent, minimize and/or effectively respond to the diverse needs of older people with disabilities.

Graphical abstract

Keywords

Dehumanization; infantilization; person-centered care; stigmatization; stereotypical attitudes; quality of care

1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to call the aged care sector into action on two accounts. First, there exists the need to fully face the ugly realities surrounding the persistent, damaging and pervasive instances concerning ageism, abuse and neglect of older people with disabilities. Second, there is the need to foster high standards of sustained quality care and safety for older disabled persons. For the sake of clarity, the aged care sector has been taken to broadly apply to an industry that provides older people with a range of different levels of health services as they age. It must be recognized that as a health service industry, the aged care sector has a large and varied workforce that contributes substantially to a country’s economic system. As a total entity, the aged care sector must accept responsibility for the wellbeing, safety and dignity of older people who access its respective health care services. Titchkosky [1] reminds us that “The presence of disability throws into question what being in or out, marginalized or mainstreamed, controlled or empowered means”. It is interesting that the World Health Organisation [2] states quite categorically that “Many older adults maintain good functional ability and experience high levels of well-being despite the presence of one or more diseases”. It is therefore quite erroneous and morally incorrect to assume that being old and disabled will automatically mean that the individual is frail and dependent. However, older people with limited or severe dysfunction in one or more ‘key capability’ domains [3,4,5] will more than likely, at some time, experience either minor or serious difficulties of one kind or another in human performance areas relating to a) activities of daily living (ADLs) such as those relating to personal care and b) instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) that include shopping, household chores and outside social activities that allow for engagement in a range of leisure or health related activities that assist the individual to pursue a desired lifestyle [6].

In more recent times there has been a movement away from such sayings as ‘handicapped’ or ‘impaired’ to the modern saying ‘person with a disability’ thereby offering a more balanced, progressive and humanistic focus on disability. The approach taken in the context of this paper will be to adopt the following definition of disability offered by the World Health Organisation [7] “In the context of health experience, a disability is any restriction or lack (resulting from an impairment) of ability to perform an activity in a manner or within the range considered normal for a human being”. In adopting the preceding definition of disability, it is worth noting the following perspective offered by Stone [8] “we need to demystify the phenomenon of disability, and we need to challenge the myth that disability necessarily entails dependence”.

The demographic changes occurring worldwide resulting in the rapid growth of aging populations will warrant a re-conceptualization of the meaning of old age and disability. Human disability is the result of single or multiple causes and is best considered from a life course and quality of life perspective that allows us to see that some older people in later life develop or acquire one or more forms of disability [9]. On the other hand, there are those younger people who are either born with a significant lifelong disability or subsequently develop or acquire a disabling condition(s) and then age. As a consequence, any serious examination of issues and concerns surrounding aging and disability should take note of McDaid [10] who reminds us that “In thinking about ageing and disability, it also may be useful to distinguish between those who are ageing with disability and those who acquire disabilities in old age”. Williamson and Harvey [11] note that “chronological age may not be a sufficient factor in identifying people with a disability who are ageing”. Kennedy and Minkler [12] offer a balanced viewpoint whereby they argue that human aging accommodates both the able-bodied and those with disability. It is important from the outset to understand that disability cannot be seen as a problem residing in the individual alone, it must also be seen as a co-related issue for the society in which the disabled individual lives.

2. The Problem

It is now well known around the world that many older people regardless of their cultural and ethnic background suffer from ageism, discrimination, prejudice, alienation, violence and abuse [13,14,15,16,17]. The preceding infringements of rights for older people increase more so for older people with disabling conditions such as depression, mental illness and dementia in which Alzheimer’s disease is the most prevalent form. Unfortunately, the preceding forms of mistreatment of older people have continued unabated despite formulation of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights that states that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” [18]. Pillemer et al. [19] in a systematic review of the literature on elderly mistreatment and abuse found that globally there is consensus among health care systems, welfare agencies, policy workers and members of communities of widespread abuse and neglect of older disabled people. A recent report from Australia by Chirgwin [20] highlights the continuing nature of neglect and abuse of older disabled residents in aged-care facilities “AN AUDIT of Queensland aged-care facilities has found chronic understaffing and associated neglect in all 30 of the state’s federal electorates”. A response by Bita [21] in relation to the preceding report on systemic abuse and neglect of older people in aged-care facilities says it all “Out of sight, out of mind,” can no longer be the mantra for Australia’s aged-care industry”. The Prime Minister of Australia has now called for a nationwide royal commission into aged-care quality, funding and staffing.

The recent call for a United Nations convention on ‘Strengthening Older People’s Rights’ signals the urgent need for all nation states to engage policy debate surrounding contemporary issues relating to human rights for older people including the disability rights agenda [22,23]. Eymard and Douglas [24] report that ageism is prevalent across the broad spectrum of health care providers and that “Negative attitudes toward aging have the potential to influence treatment options and care for older adults”. Far too often the uniqueness of each older disabled person is neglected for the sake of convenience. The following perspective offered by Peterson [25] offers a clear validation of the uniqueness of each individual:

Here’s the fundamental problem: group identity can be fractionated right down to the level of the individual. That sentence should be written in capital letters. Every person is unique-and not just in a trivial manner: importantly, significantly, meaningfully unique. Group membership cannot capture that variability.

It is of course necessary to understand that an aged care system that is overly oriented towards profit making from ill health is essentially a ‘sickness system’ which will find it increasingly difficult to also provide high standards of quality based care for the old and disabled. Indeed, any discussion on aging and disability aimed at developing policy and healthcare practices must first and foremost recognize that with any disabling condition there resides a human person deserving of respect, dignity and opportunities to experience high quality care and safety when faced with the need to access health care services. Meyer [26] provides an important perspective on disability that has implications for policy makers and health care providers “A general consensus has emerged that non-recognition of a person’s disability is a major roadblock on the way toward full inclusion of all persons”. The need for a quality of life approach for health care provision for older disabled persons is well articulated by National Seniors Australia as stated in the following extract from the Productivity Commission [27]:

…quality of life should be a fundamental goal of the aged care system. At present, however, [it] is more heavily focused on technical constraints, such as risk management, economic imperatives and rigid timetabling.

3. Three Models of Disability: An Overview

The Industrial revolution with its focus on scientific rationality and utilitarianism [28] combined with the medicalization of disability in the nineteenth century attributed a ‘blame the victim mentality’ and as a consequence many disabled people were marginalized or institutionalized with many experiencing negative, harmful, unethical and human rights abuses. The attitude toward disabled persons at the closure of the 19th century was extremely negative and fostered the unfortunate view that the “poor, the unemployed, the mentally ill, the mentally retarded were somehow responsible for their own fate” [29,30]. Over time three models of disability have evolved that provide conceptualizations, understandings and perspectives relating to disability. The first model can be described as the ‘individual or medical model’ of disability. According to Trani and Dubois [31] this model “is based upon the view that disability is the result of a distinction from a physical norm. In this conception, disability is considered as a physical condition which is intrinsic to the individual”. Under this model the responsibility essentially resides with the disabled person and his / her support networks of family and friends and quality of life outcome is circumscribed by the extent to which participation in community and social life can approximate what is considered ‘normal functioning’ [32]. This model has been criticized because of its limited focus on the physical and / or intellectual disability of the individual and places the burden of coping essentially on the disabled person [33,34].

The second model of disability is called the ‘social model’ and sees people with disabilities as displaying differential abilities resulting from differences in individual life circumstances and health condition restrictions. In particular, this model is concerned about the vast array of barriers that exist within specific social contexts that limit or prevent disabled persons participating in the mainstream of social activities including education, work, and leisure pursuits. Oliver [35] claims that it is society itself that must be prepared to examine itself and where necessary redesign the physical and social environment in order to facilitate greater involvement of disabled people in social life. According to Trani and Dubois [31] “the advocates of the ‘social model’ consider that physical limitations become disability because the society does not accommodate differences, i.e. it is the society which is not adequately structured”. Work undertaken by Morris [36] and Oliver and Barnes [37] point to the need for building strong advocacy strategies for improving citizenship policies for disabled people.

The third model of disability builds upon the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health known as ICF [38] and is based upon the assumption that disability is primarily “a combination of individual, institutional and societal factors that define the environment within which a person with impairments evolves” [31]. For people like Finkelstein [39] “you see disability fundamentally as a personal tragedy or you see it as a form of social oppression”. Shakespeare, Lezzoni and Groce [40] emhasize that “disability is at least as much a product of social structures and social relations as it is a result of bodily dysfunction”. The factors offered by the third model cannot be ignored when undertaking studies on disability. A consideration of poverty, housing conditions, accessibility to health and care services must necessarily be part of any serious discussion on the cultural meaning of disability [41,42,43] provides a socio-cultural perspective on disability:

If it is accepted that disability is located not solely within the mind and body of an individual, but rather in the relationship between people with particular bodily and intellectual differences and their social environment, then greater focus may be placed on ameliorating disability through changes in social policy, culture and institutional practices.

4. Framing Disability as a Cultural Construct

Extending our knowledge of aging and disability in a socio-cultural framework offers the opportunity to a) enhance awareness and understandings of how existing social, economic and physical barriers influence accessibility to health services and lifestyle activities and b) gain an appreciation of the cultural representations of disability across the life course, particularly in later life. Meyer [26] argues that while disability is now a worldwide concern he also emphasizes that “disability continues to be viewed differently by different cultures and societies”. Groce [44] makes the point:

As an anthropologist, it is always tempting to list dozens of interesting examples of the different ways in which societies have interpreted what constitutes a disability and what it means to be disabled. However, it is equally important to establish some frameworks within such beliefs and practices can be understood.

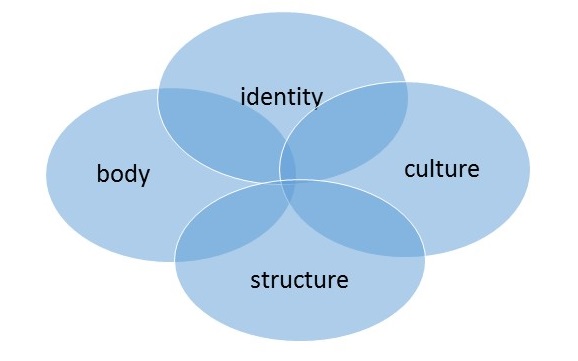

The preceding viewpoint has obvious implications for social and educational policy across different cultures. Barriers to accessibility are either real or perceived obstacles that make life difficult or often impossible for people with disabilities to engage in a meaningful and productive lifestyle. Indeed, the barriers to accessibility for both young and older disabled people include but are not limited to: attitudinal, technological, organizational, architectural or physical through to information and communication. Understanding disability in a socio-cultural context also requires an appreciation of the different levels of perception held by the community as well as older disabled persons themselves. According to Trani and Dubois [31], the approach to understanding disability should consider both cultural and social contexts as an effective and important approach for “looking at the individual within a context, a community and society as a whole”. Figure 1 illustrates the need to recognize and understand the complex and dynamic interactions between self-identity, body image, culture and social structures when thinking about aging and disability. The preceding ways of thinking about aging and disability must necessarily be considered within a life course framework that acknowledges aging as a dynamic process that is both a personal and uniquely existential experience.

Figure 1 A way of thinking about aging and disability [45].

Groce [46] contends that knowledge of traditional cultural beliefs and concepts surrounding disability can assist health care professionals to plan and implement more positive action interventions that benefit both the disabled and the wider community. Sokolovsky [47] is a strong advocate for the adoption of a focus on the cultural context and argues that while efforts “to increase positive health outcomes is never a simple matter, but must always be undertaken by first understanding the culture system from the inside”. Culture is considered as a way of thinking and living. According to Bourdieu and Wacquant [48] once social structures are formed they in turn influence the subconscious domain of individuals by shaping their way of thinking, perception and behavior. However, their ‘habitus’ or set of socially learned dispositions and ways of acting and thinking are not entirely fixed or determined but wax and wane as a consequence of inner tensions arising through their subjective struggles. These subjective or existential struggles are part of each individual’s attempt to enhance his / her opportunities to acquire economic, cultural, social and symbolic capital in the social realm. Despite differential levels of power and advantage every individual joins this struggle. While differentiation is a part of the struggle for capital it also helps to explain aspects of inequality and discrimination in lowering the opportunities for disabled persons to acquire sufficient social and symbolic capital for quality of life outcomes [48]. For Bourdieu [49] “the accumulation of economic capital merges with the accumulation of symbolic capital, that is, with the acquisition of a reputation for competence and an image of respectability and honourability…”. Recognition must also be given to the fact that the individual's body is an integral part of the competition or struggle for social and symbolic capital. It is easy to see, that for the majority of physically disabled persons, including those made vulnerable by the passing of time, that they will find it extremely difficult within the context of a specific set of socio-cultural structures to build a portfolio of social and symbolic capital. According to Titchkosky [1] disability “is more insofar as it is the embodiment of an alternative way of being steeped in the fact that the disabled body is situated between all the stuff a culture gives to its people”. It must also be recognized that disabled older persons will encounter more disadvantages than their counterparts who may have higher functional status and health. However, there are those younger and older people who despite illness or disability are creative and enterprising and as part of their established ‘habitus’ and subjectivities are both flexible and able to circumvent many of the limitations and disadvantages allied to disability [50,51].

In the search for clarity of meaning, ‘normality’ and ‘disability’ are frequently interpreted as being opposite [52,53]. Cultural definitions of disability are based on categorization and differentiation of the body. These cultural categories are ideological on the basis of differentiations and could be listed according to Polat [53] as: sick, deformed, crazy, ugly, old, crippled, afflicted, abnormal, and weakened. Either way, the body is observed by others and for the individual is understood, experienced and compared in relation to what is culturally deemed normal or desirable. As a consequence, the body is part of the social critique and generally judged in accordance with appearance, representation and labeling which can be positive or negative. Stigmatization of disabled persons is one form of discrimination and can influence social consciousness leading in turn to detrimental levels of antagonistic and negative association with disability. At the same time, stigmatization can result in affecting the self-perceptions of older disabled individuals to the extent that they perceive themselves to be a failure and useless with negative outcomes for self-identity, behavior and health. In this respect, social and symbolic capital losses within specific cultural settings may be sufficient to affect how individuals with disability see themselves leading often to poor self-image, despair and low adaptive capacity. According to Coleman [54] a “culture’s expectations of older people’s roles within a society have a vital place in encouraging or inhibiting personality change in later life” [55].

The most important transformation in history shaping cultural systems is the transition from traditional to modern life brought about by modernization and its counterpart globalization. Western societies and more recently less developed societies have experienced the medicalization of human life [56] including a focus on disability as part of the expansion of medical categories and treatment regimens. Unfortunately, there exists culture wide practices that promote paternalism as well as instances of human rights abuses and neglect. According to Oliver [57] the tendency for capitalist societies to emphasize individualism, success and independence can often lead to negative attitudes and discriminatory practices against disabled individuals [28]. Triandis [58] describes individualism and collectivism as the most important cultural characteristics which can affect social behavior. According to Hofstede [59,60] “The individualistic cultural pattern is found in most northern and western regions of Europe and North America, whereas the collective pattern is common in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Pacific” [61]. Meyer [26] makes the point that while both individualistic and collectivist cultures provide assistance to the disabled it is the individualistic culture that has adopted a “rights-based approach to disability”. Meyer also reports that an orientation towards integration and inclusion of disabled people based on equal rights is more common in individualistic type cultures while segregation of the disabled is more characteristic of collectivist cultures. Hofstede [62] offers an important paradigm for comparing cultural differences with implications for future research undertakings. Waldschmidt [63] argues that culture is one of the most important factors in the socio-cultural construction of meanings and attitudes towards disability. Darwish and Huber [64] offer the view that “people with an individualistic cultural background will have more private self-cognitions and fewer collective self-cognitions than people from a collective cultural background”. Therefore, it can be expected that a more differentiated and personalized view of disability is more likely to exist in individualistic cultures compared to collective cultures. For those decision makers involved in designing and implementing programs for the disabled an awareness and understanding of how different cultural and political dynamics impact the level of support and wellbeing of disabled persons is imperative. Komardjaja [65] using Indonesia as an example, speaks of how inadequate public infrastructures and social policy limit the visibility of disabled persons and accordingly offers the following commentary:

The ideal of a ‘barrier-free’ environment is promoted in developed countries as a means of increasing the independence and mobility of disabled people. The adoption of this concept for developing countries requires critical analysis.

The difficulty of understanding disability is made even more so when examining specific cultures and compounded further as not all societies adhere entirely to the view of Finkelstein [39] “that disability is entirely socially imposed and amounts to a form of social oppression” [66]. As the social and cultural meanings and perceptions of disability and illness are not consistent from society to society it is therefore important to note the advice of Thomas [66] that it is best “to provide a better fit between divergent cultural models of disease and the modern health care system”. While the general perception of disability across societies may be different [67] it is important not to assume that socio-cultural belief systems relating to disability remain static, particularly among traditional cultural groups [44]. When traditional cultures engage with developed countries through modernization and globalization processes longstanding beliefs and customs surrounding disability can change over time and in some cases very quickly. Hunter et al. [68] draw attention to the transformation difficulties encountered by people from different countries when entering the United States and trying to reconcile their traditional health beliefs and customs with unfamiliar health care systems and practices. In this regard, it is important for health care providers to be sensitive to both language difficulties of new immigrants including the likely confusion and anxiety associated with medical terminology and health care management practices. Groce [44] calls for a heightened sensitivity among aged care workers when attending to the health needs of older people from different cultures:

People undergoing social change rarely abandon everything they know and everything they practice, in order to unquestionably adopt a new system of thoughts, beliefs and behaviours. Rather, as international health and developmental agencies are increasingly coming to realise, new and old ideas often co-exist and frequently co-mingle, producing hybrids that are neither wholly the old nor the new system.

Culture has a past, present and future and the impact of external influences such as education and changing levels of information open up new ways of thinking and behaving in relation to such matters as health, illness and disability. It is not uncommon for dominant cultures and more powerful ethnic groups to dominant or repress less powerful cultural and ethnic entities in a specific social system. As a consequence, specific cultural and religious customs and belief systems are often imposed and exaggerated, particularly in closed societies, and especially in crisis type situations. Social identity is based on factors such as ethnicity, gender, class, and caste which interact to form particular ways of thinking and behaving including the adoption of belief systems and approaches to health, illness and disability [33]. It should not be overlooked that culture is not independent from economic, political and social conditions and while there may be acceptance of more progressive models and approaches to disability and health care the lack of appropriate access to necessary resources and support services may result in the maintenance and / or return to more traditional “belief models” [44]. Therefore, efforts undertaken to understand the cultural meaning of aging and disability should examine existing approaches and practices including, the level of development and provision of policies and services aimed at supporting the disabled.

5. The Aged Care Sector: Abuse Born of Ageism

The ubiquitous ‘decline’ narrative in relation to the aging process puts disabled older people at a considerable disadvantage when matched against the ‘successful aging’ narrative including allied descriptors ranging from ‘positive aging’, ‘healthy aging’, ‘productive aging’ and ‘aging-well’. Depp and Jeste [69] in a comprehensive review of the literature on successful aging report “That the most frequent correlates of the various definitions of successful aging were age (young-old), non-smoking, and absence of disability, arthritis and diabetes”. Perhaps it is timely to ask: ‘Is the current definition of successful aging disqualifying a small but growing segment of the older population who are disabled, poor and frail’? More importantly, the ‘idealized’ image of successful aging being aligned with autonomous and independent living does no justice whatsoever to those who may be living with a major disability and / or chronic illness. Minkler [70] likewise argues that “Concepts like healthy or successful ageing used unintentionally, can contribute to stigmatization and disempowerment of those who fail to meet our criteria for ageing well”. In other words, the effort to make aging synonymous with success may be unwittingly creating the unfortunate situation whereby those older people who cannot fit the criteria for ‘successful aging’ may be viewed negatively resulting in unwarranted stigma and the adoption of the term ‘failed aging’. Featherstone and Hepworth [55] remind us that “Ageism, then refers to a process of collective stereotyping which emphasizes the negative features of aging which are ultimately traced back to bio-medical “decline” rather than the culturally determined value placed on later life”. Thomas and Chambers [71] in a study of ‘Successful Aging’ Among Elderly Men in England and India highlighted the importance of “examining cultures which provide widely differing environments and values relevant to the handling of old age”. Moody [72] supports the preceding view by arguing that our contemporary understandings of ‘successful aging’ pay little or no serious attention to the importance of the cultural context which impacts the lives of people as they age. Thomas and Chambers [71] drawing upon the earlier research contribution of Clark and Anderson [73] in Culture and Aging: An Anthropological Study of Older Americans highlight the finding that there tends to be less stress upon the aging individual in “Cultures in which dominant value-orientations are more consonant with the realities of the latter part of the life cycle (physical decline and eventual death)”. Eymard and Douglas [24] make the point that “Ageist negativity is an increasing and dangerous trend in the United States with noted secondary effects not only on provision of care but also on clinical interaction”. Teater and Chonody [74] offer an active aging framework for social work practice that challenges the notion of ‘successful aging’ by promoting programs and services that allow for collaborative processes to involve older disabled people to undertake activities that are in accord with their expressed needs, wishes and functional abilities. The aged care sector might well note the following perspective offered by the Productivity Commission [27] in Australia:

An aged care system with a focus on promoting wellness, active aging and enhancing the independence of people in later life might not only enhance the wellbeing of older people, but could also be effective in reducing demand for more expensive and ongoing services.

The work of Cuddy and Fiske [75] raises the interesting notion of positive versus negative stereotyping of older adults where there is likely to be a stronger sense of warmth and positive regard for those who meet the criteria for the contemporary concept of ‘successful aging’ compared to those who are disabled and dependent upon a range of community and health care support services. An issue of real concern is the attitude that prevails in some segments of society that sees older disabled people as a problem and a burden on the health care system [76,77,78] who have articulated the work of the renowned gerontologist Robert Butler provide an important insight on what might be termed the ‘ripple effect’ of ageism:

Butler identified three distinct but related aspects of ageism: attitudes and beliefs, behavioural discrimination, and formalized policies and practices. In essence, attitudes determine behavior, which in turn influence policy development and implementation, which in turn influence practice.

The challenges surrounding the adoption of more appropriate use of language in hospitals and residential long-term care facilities warrants urgent attention. The power of words should never be underestimated. Davidson [79] in Metaphors of Health and Aging: Geriatrics as Metaphor illustrates how the use of negative metaphors of aging can damage the well-being of older disabled patients “the individual is dissected further to reveal such metaphors of the person as, a sick heart, a fractured hip, a bowel cancer and so on. Other parts of the body are often not focused upon, and the psychological, spiritual and social spheres of the individual are quickly ignored”. According to Davidson [79] the tragic outcome of treating the aged patient ‘in parts’ will frequently lead to the dehumanization of the older patient. Stone [8] makes the claim that “Both the “aged” and the “disabled” are commonly conceptualized as essentially frail, and these reified groups … are also conceptualized as essentially dependent”. The same researcher throws out a strong message particularly directed to health care professionals “pay attention to how people define themselves, rather than rely too closely on reified constructions of what people are or are not supposed to be able to do”. Roos [80] provides an alarming commentary that has serious implications for older disabled persons “Ageing is very often regarded as a kind of extended terminal illness.

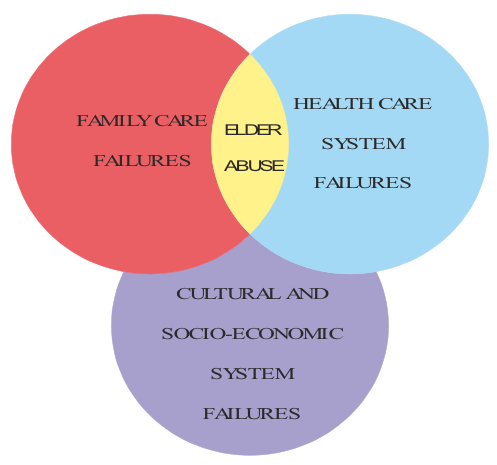

Schumacher, Jones and Melios [81] identify the need for health care professionals to understand the importance of focusing on the transitions that older people will make as a consequence their changing health needs. This approach will have consequences for the type of support services and resources that will need to be utilized in order to provide effective and humane care. Darzins and Marriott [82] speaking in relation to medical treatment of older people infer that “Inspection of patients’ circumstances through the ‘lens’ of the major principles of bioethics can provide insights that guide treatment decisions”. Figure 2 shows a triad of social system domains that either independently or through a complex mix of interactive processes create sources of elder abuse and exploitation that stem from the pervasive influence of ageism leading to infringements on human rights. As HelpAge International [83] point out:

All societies discriminate against people on the grounds of age. Ageism and stereotyping influence attitudes, which in turn affect the way decisions are taken and resources are allocated at household, community, national and international levels.

The level of disadvantage becomes even more so if gender is taken into account. The problems encountered by older disabled women in later life is illustrated by Holcomb and Giesen [84] in their study of older disabled women going to college who spoke in one way or another about “the burden of triple jeopardy / triple discrimination: sexism, ageism, disablism”. Of course, there is also the possibility of multiple jeopardy if due consideration is also given to issues such as poverty, and ethnic minority status [85]. Johnstone and Kanitsaki [86] talk about the disparities in health and social care as a matter of social justice arising from the presence of ‘cultural racism’ directed towards people who are old and of a minority ethnic and language background. It was Wirth [87] who helped in defining minorities as “a group of people, who because of physical or cultural characteristics, are singled out from others in society for differential and unequal treatment, and who therefore regard themselves as objects of collective discrimination”. Drawing upon the experience of the eminent French psychologist and psychotherapist Marie de Hennezel [88] in her work with older terminally ill patients she found that acts of violence against some patients varied in nature and “may be physical (blows, slaps) but also verbal (insults, threats) or psychological (mental cruelty, humiliation, harassment, failure to respect privacy, refusal of visits, confiscation of mail etc)”. She also referred to instances involving theft and fraud as well as over medication and frequent bouts of hurried and brutal washing regimes.

Figure 2 Areas of real or potential abuse of older disabled people arising from ageism leading to infringements of human rights.

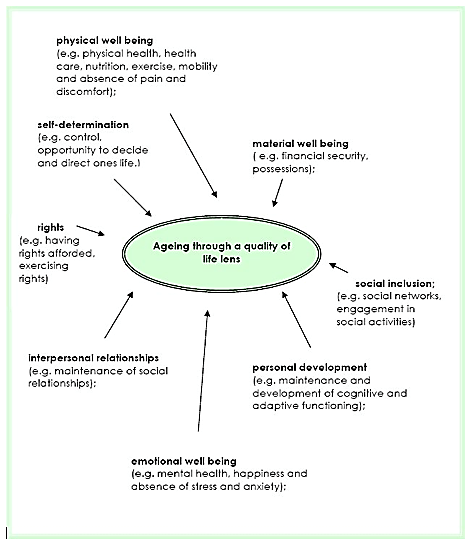

Figure 3 is offered as a way of promoting an exercise of self-reflection among healthcare workers on the range of quality of life domains that we all hold as sacrosanct throughout our own life course and which have been articulated in various forms through publications undertaken by the World Health Organisation under the rubic of Human Rights. It might also be useful to question how these respective life quality domains may be compromised for those persons with chronic diseases and disabilities across the life course and particularly into later old age. Paternalistic interventions on behalf of the aged often stem from negative or pejorative stereotyping of older persons [89]. Jamieson et al. [90] refer to the work of Turner [91,92] in a manner that holds weight for the preceding challenge “Older people are, according to Turner, in competition with other social groups because the negative experience of aging results in them being denied their universalistic rights of citizenship”. The Australian Human Rights Commission [93] is a strong advocate for the adoption of a human rights approach which applies directly to the provision of aged care health services whether to community dwelling dependent older people or those in residential aged care and includes “four interrelated and essential components: Availability, Accessibility, Acceptability and Quality”. The words of Martin Luther King (Jr) seem relevant in the present context ‘A right delayed is a right denied’. It is important for family carers, and aged care staff assigned to work with disabled older adults in hospitals and aged facilities to heed the words of de Hennezel [88] “The argument that there is a shortage of time and staff in aged-care establishments is often trotted out, erroneously, as an excuse for the absence of humanity. Being humane does not take more time. On the contrary, when you are truly there for the other person, you discover that you can do the same thing, but better, and in the same amount of time”. Carnell and Paterson [94] in an examination of regulatory processes in residential care settings for the aged highlight the problems arising from polypharmacy and medication errors that occur far too often. At the same time, there are issues relating to a) drug theft in long-term aged care facilities and hospitals resulting in older patients receiving less than the prescribed medications for their medical condition and b) financial exploitation by either family members or aged care workers.

McCarthy [95] provides a range of guidelines for both family and professional carers of older persons with dementia based upon person-centered approaches. Although person-centered care is not new the guidelines provide a timely reminder that all too often the continuing and relentless demands of caregiving within family or institutional contexts can unintentionally result in the depersonalization of the older disabled individual. The next several decades will see increasing numbers of people aged seventy-five years and older resulting in added numbers of people with dementia. This fact alone will mean that the increased demand for family caregiving will in all likelihood contribute to a rise in the prevalence of abuse of older people [96,97,98]. A damning testimony is provided by de Hennezel [88] who provides the following anecdotal account offered by an older female resident in a nursing home “Everyone does their work according to the established protocols, without taking any account of the patient’s wellbeing. They work with their arms, but their heads and hearts are missing”. A genuine person-centered approach requires both empathy and imagination combined with a sensitive and respectful communication style that is calm and confident and can be an important means for carers to protect the overall dignity and personhood of the older disabled person [95]. The United Nations [99] ‘Principles of Older Persons’ provides a clear statement on the rights of older people living in residential care settings or in receipt of health care related services:

Older persons should be able to enjoy human rights and fundamental freedoms when residing in any shelter, care or treatment facility, including full respect for their dignity, beliefs, needs and privacy and the right to make decisions about their care and the quality of their lives.

Figure 3 A quality of life lens for understanding aging and disability across the life course [11].

6. Aging and Disability: Challenges for the New Millennium

There is no doubt that comparative studies will show that the way we live our daily lives both now and in the foreseeable future will show lifestyle orientations significantly different from any other time in our evolutionary history. The World Health Organisation [100] in Global Age-friendly Cities: A Guide reports that “Population ageing and urbanization are two global trends that together comprise major forces shaping the 21st century”. In a very practical way, the preceding WHO publication aims to encourage cities around the world to tap into the potential of older people by identifying and removing barriers that prevent healthy living and participation in community life by adapting their respective “structures and services to be accessible to and inclusive of older people with varying needs and capacities”. The processes involved in modernization and the burgeoning growth of cities around the world has and will continue to produce social and economic changes that are unprecedented in world history. While the traditional ‘individual or medical model’ sees disability as an intrinsic condition that resides in the individual the more realistic ‘social model’ of disability tends to consider the existing barriers that disadvantage the individual with a disability [31]. In essence, society itself must take a significant measure of responsibility for redesigning social systems and allied infrastructures in order to benefit the wellbeing of persons with disabilities. The link between environmental design and public health issues such as chronic diseases, including Type 2 diabetes, heart disease and respiratory illness has recently been identified as a prime area of focus by the Legislative Council of the Parliament of Victoria-Australia in a final report Inquiry into Environmental Design and Public Health in Victoria [101]. In particular, this report emphasizes the importance of considering health in the design of our communities, such as: “creating environments that promote physical exercise and social interaction; providing access to healthy, fresh food; facilitating access to green and other open public spaces; and ensuring inclusivity and accessibility in the built environment. Such health promoting elements can be purposely designed into the built environment, or, as is too often the case, designed out”.

Darton-Hill and James [9] taking a life course approach emphasize that the scale of contemporary social, economic and technological advances have inadvertently resulted in an increase in sedentary lifestyles across all ages evidenced by declining physical activity patterns and poor dietary regimes with consequent increases in the incidence of obesity and diabetes. Nisoli and Carruba [102] speak of globesity as a means of drawing our attention to the fact that obesity in this day and age has to be recognized as a “multifactorial, chronic disorder that has become a global epidemic”. Darton-Hill and James [9] provide an alarming scenario for the future “The number of people in the developing world with diabetes will increase more than 2.5 times (from 84 to 228 million) in 2025”. The dynamics associated with the preceding trends will result in an increase in chronic disease patterns and in turn present a myriad of service and health care system challenges worldwide. Clarfield, Bergman and Kane [103] point out that it is generally the case that “the frail elderly often suffer from a combination of multiple, chronic diseases as well as social problems, necessitating a team approach to both diagnosis and management”. Fried et al. [104] report that “frailty is distinct from, but overlapping with, both comorbidity and disability. In addition, both frailty and comorbidity predict disability, adjusting for each other; disability may well exacerbate frailty and comorbidity, and comorbid diseases may contribute, at least additively, to the development of frailty”. It is also noteworthy, however, that Clarfield et al. [105] report that in developed countries there appears to be not only a decline in mortality rates even into later age but successive cohorts of older people are displaying improved levels of good health and overall function. The same researchers are less confident that the same can be said for less developed countries as insufficient information exists to allow for comparative studies. While dementia related disorders in old age represent a universal phenomenon, Politt [106] warns that future research undertakings will be needed to explain if there are any marked differences across cultures and between social and ethnic groups.

Guralink [107] speaking primarily about the United States announced what is now becoming a worldwide phenomenon that “The future population will be increasingly older due to increased life expectancy as well as the demographic trends related to the aging of the “baby boom” generation”. However, will living longer translate into living longer with chronic health related problems and disability? Fries [108] raised an interesting proposition that it is possible that “The amount of disability can decrease as morbidity is compressed into the shorter span between the increasing age at onset of disability and the fixed occurrence of death”. This preceding proposition heralded the beginning of the “Compression of Morbidity Hypothesis” versus the “Expansion of Morbidity Hypothesis” [109]. The preceding hypotheses need to be considered in terms of the research on disability occurring in later life which has “identified non-modifiable risk factors such as age, gender and genetics, and modifiable risk factors such as age-related diseases, impairments, functional limitations, poor coping strategies, sedentary lifestyles and other unhealthy behaviors, as well as social and environmental obstacles” [110]. The leading causes of death among older people are cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and respiratory disease and these four non-communicable diseases share a common relationship with the same group of modifiable risk factors, namely: low levels of physical activity, smoking, alcohol use and diets high in salt and fat [111]. Heuser and Hazzard [112] provide a realistic yet encouraging assessment of aging and the onset of disability “As the number of elderly individuals increases, so will the prevalence of chronic disease, disability and dependency. However, recent medical literature is replete with evidence that lifestyle and medical choices made early in life can have a profound effect on the prevalence and severity of disability and chronic disease in this geriatric population”. At the same time, there is every reason to believe that appropriate lifestyle adjustments in older age can also enhance the potential and possibility for improved health and well-being outcomes. Of course, there must be sustained efforts to draw upon emerging research evidence to “dispel the old myths that the risk of disease is a normal part of old age and not amenable to change, and that an old body cannot respond positively to lifestyle changes” [110].

Future strategic initiatives need to be formulated on the following advice offered by Heuser and Hazzard [112] “Thus to decrease the level of disability in elderly persons, physicians must focus attention on lifestyle choices made by younger adults today”. The preceding approach needs also to take on board “the new emerging knowledge about modifiable risk factors and effective interventions” [110]. While health promotion agencies should be encouraged to adopt a life course approach in the development of policies and programs aimed at preventative health strategies they should also ensure that they are inclusive of older people. In addition, each respective country around the world will still need to undertake an assessment of the resource implications for the provision of services relating to people with disability as they age. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [113] provide an important message for service providers working to support the needs of older disabled persons “As people with a disability age, they may encounter service ‘grey areas’. That is, it may not be clear what services are most appropriate to meet their changing needs, or services that meet their needs may not be available”. Gawande [114] argues that despite the advances in modern medicine and allied technologies there exists a reluctance to “honestly examine the experience of aging and dying”. Any society claiming humanitarian concerns for the aged will need to be in a position to demonstrate that they have in place responsive policies, services and practices that aim to prevent, minimize and respond effectively to the diverse needs of older people suffering from chronic illness and / or disability.

The establishment quality based health related services and care for the diverse needs of an aging population represents an important and ethically responsible action on the part of nations throughout the world. However, there are inherent dangers for those who are frail, chronically ill and or disabled when they have to navigate a complex health services field comprising a series of multidisciplinary interventions. The degree of vulnerability associated with the task of negotiating the maze of non-integrated health services “is shaped or exacerbated by inequalities, disempowerment or access to social protection” [115]. Failure to negotiate the complexities and political agendas residing in a non-integrated health care system can often lead to unintended and unrecognized elder abuse. The preceding issues will require contextualized responses and solutions from all countries around the world as they concern health-related human rights. The World Health Organisation [2] offers the following perspective on health care systems “Moreover, health care that considers and manages the complex needs of older people in an integrated way has shown to be more effective than services that simply react to specific diseases individually”. Miles and Elliot [116] in their advocacy campaign for person-centeredness in health and social care provide a timely commentary for health care providers:

Indeed, despite the inexorable rise of the patient as sovereign consumer of health and social care services, with all of the powers and privileges such a status technically affords, the ability of patients to act as prime movers of person-centered change within care systems has remained largely underexplored, if not, by default, disallowed.

7. Conclusion

Currently there exists a dearth of critical thinking about aging and disability. Zeilig [117] proffers the view that critical gerontology offers an important opportunity to raise complex questions concerning old age and aging. For Zeilig, critical gerontology provides the means to “radically re-think the ways in which age and ageing have been culturally configured…which aims to unsettle our habitual and comfortable frameworks and needle us towards personal and cultural transformation”. Aging and disability are after all, a matter of changing our perceptions and perspectives in order to open new insights, appreciations and understandings that may help us to recognize the distinctive needs, vulnerabilities and sources of mistreatment of older disabled people [118]. Bigby [119] in relation to the stereotypical attitudes and discrimination towards older adults with intellectual disabilities notes “Many of the negative aspects of their lives do not stem from their inherent characteristics or the process of ageing per se but from age-related discriminatory societal attitudes and structures endemic in service systems”. Larsson et al. [120] make an important call for improving understandings and heightened awareness of older people experiencing demanding medical situations resulting in existential concerns and anxieties. Likewise, Taube et al. [121] identify the need to recognize and act upon the sense of loneliness often experienced by frail older persons. A cornerstone of sound ethically based aged care is the ability of carers (informal and formal) to “listen with respect and generous attention” [122]. Quality based aged care is essentially a matter of ethics, organization and human relationships.

While a life free of discrimination and ageism is a fundamental human right there still remains much work to be undertaken to challenge the underlying negative assumptions and prejudice about aging and old age across all societies. The rhetorical attachment to disability within the context of human rights is not always upheld in practice relating to aged care. It would seem reasonable and ethically appropriate that all areas encompassing the aged care sector including educational institutions responsible for the preparation of graduates for medicine and related support fields such as nursing, physiotherapy, psychology, social work, occupational therapy and gerontology be required as mandatory practice to offer appropriate training and education surrounding understandings and application of Human Rights principles [24,40,123,124]. This should also require a) understandings associated with the United Nations [125] Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities and b) the offering of training programs that raise awareness of ageist attitudes and the subsequent impact on delivery of support and care. With this thought in mind it is recommended that where obvious shortfalls exist in meeting the preceding requirements that appropriate amendments be made to established audit protocols for reviewing and evaluating the performance of health care systems and higher education institutions in order to monitor compliance.

Ongoing research must be a high priority across all areas of aging related services. At the same time, appropriate codes of conduct should be developed covering all aged care workers including the need for all aged care workers to be registered in accordance with their respective roles and responsibilities. Recruitment practices of aged care workers should also be reviewed in the interest of aiming for a balanced quality based workforce across the aged care sector. Nursing and residential care facilities should be more closely monitored for compliance to quality based service provision and subject to high standards of accreditations including mandatory reporting of resident abuse and neglect. O’Reilly, Courtney and Edwards [126] contend that despite the ambiguities surrounding the concept of quality care in residential aged care facilities that it should be operationalized in the interest of judging and comparing the overall standards of residential care facilities. Deloitte Access Economics [127] report that the increasing complexity of aged care will have significant consequences for the aged care workforce and further note:

In addition, advances in medicine and patient care mean that continuous training and skills development are necessary in the aged care workforce. These advancements mean that in order to provide best practice patient management and residential care services, workers must be updating their skills on an ongoing basis, particularly in areas where boundaries are often challenged and new areas explored such as managing patients with cognitive issues.

A unique feature of a publication by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and HelpAge International [128] entitled Ageing in the 21st Century: A Celebration and A Challenge offers the view that “Policymakers are more likely to frame policies and vote resources for older people if they themselves view older persons in a positive light”. The challenge for health care providers in terms of aging and disability is to find opportunities for interventions at the level of attitudes, policy and practice that facilitate for each older individual “positive aspects of aging, of potentials, and of hope” [129]. Coulter [130] provides us with a telling and challenging commentary “We risk categorizing the elderly as a by-product of life with a rapidly diminishing value”. In particular, the field of geriatric medicine is challenged by Davidson [79] to undertake the challenge of humanizing its operational mandate by way of adopting the following orientation to health care service and delivery:

The essence of geriatric medicine lies in the capacity of an interdisciplinary team to view the aged patient as a dynamic, whole individual; to view him or her as a physical, psychological, spiritual, and social being. In this model, it is the geriatric team’s goal to optimize the aged individual’s living conditions.

Author Contributions

Overall the work to produce, revise, critique and complete the manuscript amounted to an equally shared contribution by the respective authors.

Funding

The work was initiated and completed as a non-funded professional project by way of shared commitment by the respective authors.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Titchkosky T. Disability, self, and society. London: University of Toronto Press; 1966. [Google scholar]

- World Health Organisation. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2015; 18000516. [Google scholar]

- Nussbaum MC. Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice. Fem Econ. 2003; 9: 33-59. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Nussbaum MC. Frontiers of justice: Disability, identity, species membership. Cambridge: Belknap Press; 2006. [Google scholar]

- Zola IK. The elderly-legal and ethical issues in healthcare. New York: Routledge; 2016. [Google scholar]

- Gu D, Gomez-Redondo R, Dupre ME. Studying disability trends in aging populations. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2015; 30: 21–49. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. International classification of impairments, disabilities and handicaps. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1980; 9241541261. [Google scholar]

- Stone SD. Disability, dependence, and old age: Problematic constructions. Can J Aging. 2003; 22: 59-67. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Darton-Hill I, James WPT. A life course approach to diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Public Health Nutr. 2004; 7: 101-121. [Google scholar]

- McDaid S. Mapping issues for policy and practice in the Irish setting. Seminar Proceeding: The Interface Between Ageing and Disability; 2006 February 6; Dublin, Ireland. [Google scholar]

- Williamson M, Harvey T. Ageing successfully in place. Osborne Park: National Disability Services Western Australia; 2007. [Google scholar]

- Kennedy J, Minkler M. Disability theory and public policy: Implications for critical gerontology. International Journal of Health Services. 1998; 28: 757-776. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Angus J, Reeve P. Ageism: A threat to “ageing well” in the 21st century. J Appl Gerontol. 2006; 25: 137-152. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Age discrimination - exposing the hidden barriers for mature age workers. Sydney: Public Affairs/ Australian Human Rights Commission; 2010. [Google scholar]

- Feldman S. ‘Please don’t call me dear’: Older women’s narratives of health care. Nurs Inq. 1999; 6: 269-276. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- James M. Abuse and neglect of older people. Fam Matters. 1994; 37: 94-97. [Google scholar]

- Pillemer K, Finkelhor D. The prevalence of elder abuse, a random survey. Gerontologist. 1988; 28: 51-57. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Assembly, UN General. Universal declaration of human rights. UN General Assembly; 1948. http//www.un.org/Overview/rights.html (cited date: 2012, June10).

- Pillemer K, Burnes D, Riffin C, Lachs M. Elder abuse: Global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies. Gerontologist. 2016; 56: S194-S205. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Chirgwin S. ‘Neglect and staff shortages rife’ in aged-care homes. Queensland: The Courier-Mail, p.7; 2018, September 15. [Google scholar]

- Bita, N. Ugly tales of neglect. Queensland: The Courier-Mail, p.21; 2018, September 18. [Google scholar]

- Huxley P, Thornicroft G. Social inclusion, social quality and mental illness. Brit J Psychiat. 2003; 182: 289-290. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- UN General. Rights of Older People. Report of the Expert Group Meeting. Bonn: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Division for Social Policy and Development, Programme on Ageing; 2009. [Google scholar]

- Eymard AM, Douglas D. Ageism among health care providers and interventions to improve their attitudes toward older adults: An integrated review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2012; 38: 26-35. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Peterson JB. 12 rules for life: An antidote to chaos. New York: Penguin Random House; 2018. [Google scholar]

- Meyer HD. Framing disability: Comparing individualist and collective societies. Comp Sociol. 2010; 9: 165-181. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Productivity Commission. A literature review and description of the regulatory framework. Australia: National Seniors Australia; 2011; No. P3-2088. [Google scholar]

- Westbrook MT, Legge L, Pennay M. Attitudes towards disabilities in a multicultural society. Soc Sci Med. 1993; 36: 615-623. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick CH. Two for the price of one: Accessibility and usability. Comput Libr. 2003; 23: 26-30. [Google scholar]

- Thornberry C, Olson K. The abuse of individuals with developmental disabilities. Dev Disabil Bull. 2005; 33: 1-19. [Google scholar]

- Trani JF, Dubois JL. Capability and disability: An approach for a better understanding of disability issues. A Pre- Conference Workshop paper as part of a UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: A Call for Action on Poverty, Lack of Access and Discrimination; 2018 May 19-22; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google scholar]

- Marks D. Disability: Controversial debates and psychological perspectives. London: Routledge; 1999. [Google scholar]

- Coleridge P. “Disability and Culture”: Disability, liberation and development. London: Oxfam and ADP; 1993. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Grönvik L. Defining disability: Effects of disability concepts on research outcomes. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2009; 12: 1-18. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Oliver M. Understanding disability: From theory to practice. Basingstoke: Macmillan; 1996. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Morris J. Citizenship and disabled people: A scoping paper prepared for the Disability Rights Commission. London: Scope; 2005. [Google scholar]

- Oliver M, Barnes C. Disability studies, disabled people and the struggle for inclusion. Brit J Soc Educ. 2010; 31: 547-560. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- World Health Organisation. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010; 9241545429. [Google scholar]

- Finkelstein V. A personal journey into disability politics. Leeds: Centre for Disability Studies, University of Leeds; 2001 [cited date (2012 August)]. Available from: www.leeds.ac.uk/disability-studies/archiveuk/archframe.htm. [Google scholar]

- Shakespeare T, Lezzoni L, Groce N. Disability and the training of health professionals. Lancet. 2009; 374: 1815-1816. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Dunn DS. Teaching about psychosocial aspects of disability: Emphasizing person–environment relations. Teach Psychol. 2016; 43: 255-262. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Trani JF, Loeb M. Poverty and disability: A vicious circle? evidence from Afghanistan and Zambia. J Int Dev. 2012; 24: 19–52. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Marks D. Models of disability. Disabil Rehabil. 1997; 19: 85-89. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Groce NE. Guest Editorial: Framing disability issues in local concepts and beliefs. Asia Pac Rehabil J. 1999; 10: 4-8. [Google scholar]

- Priestley M. Adopting a life course approach to ageing and disability. Seminar Proceeding: The Interface Between Ageing and Disability; 2006 February 6; Dublin, Ireland. [Google scholar]

- Groce NE. Disability in cross-cultural perspective: Rethinking disability. Lancet. 1999; 354: 756-757. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Sokolovsky J. The Cultural context of aging: Worldwide perspectives. Westport: Praeger Publications; 2009. [Google scholar]

- Bourdieu P, Wacquant LJD. An invitation to reflective sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste (Translated by Richard Nice). Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1984. [Google scholar]

- Gatrell A, Popay J, Thomas C. Mapping the determinants of health inequalities in social space: Can Bourdieu help us?. Health Place. 2004; 10: 245-257. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Gullette MM. Aged by culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. [Google scholar]

- Gray C. Narratives of disability and the movement from deficiency to difference. Cult Sociol. 2009; 3: 317-332. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Polat ÇS. The cultural descriptions of disabled people through the movie “Baska Dilde Ask” MS thesis. Ankara: Hacettepe University; 2011. [Google scholar]

- Coleman P. An Introduction to Social Gerontology. London: Sage; 1993. [Google scholar]

- Featherstone M, Hepworth M. The Cultural context of aging: Worldwide perspectives. 3rd ed. Westport: Praeger Publishers; 2009. [Google scholar]

- Maturo A. Medicalization: Current concept and future directions in a biotic society. Mens Sana Monogr. 2012; 10: 122-133. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Oliver M. Understanding disability: From theory to practice. New York: St Martin’s Press; 1996. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Triandis HC. The many dimensions of culture. Acad Manage Executive. 2004; 18: 88-93. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverley Hills: Sage; 1980. [Google scholar]

- Hofstede G. The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. J Int Bus Stud Fall. 1983: 75-90. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Han SP, Shavitt S. Persuasions and culture: Advertising appeals in individualistic and collective societies. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1994; 30: 326-350. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Hofstede G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede Model in context. Online Readings Psychol Cult. 2011; 2: 1-26. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Waldschmidt A. Culture-Theory-Disability. Bielefeld: Transcript; 2017. [Google scholar]

- Darwish AFE, Huber GL. Individual vs collectivism in different culture: A cross-cultural study. Intercultural Educ. 2003; 14: 47-55. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Komardjaja I. New cultural geographies of disability: Asian values and the accessibility ideal. Soc Cul Geogr. 2001; 2: 77-86. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Thomas C. How is disability understood? An examination of sociological approaches. Disabil Soc. 2004; 19: 569-583. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Şenel A. From primitive community to modern societies. Ankara: Bilim-Sanat; 1995. [Google scholar]

- Hunter A, Mayo R, Willoughby D. Acculturation and adherence: Issues for health care providers working with clients of Mexican origin. J Transcult Nurs. 2004; 15: 331-337. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger qualitative studies. Focus. 2009; 7: 137-150. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Minkler M. Critical perspectives on ageing: New challenges for gerontology. Ageing Soc. 1996; 16: 467-487. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Thomas LE, Chambers KO. Research on adulthood and aging: The human science approach. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1989. [Google scholar]

- Moody H. The cultural context of aging: Worldwide perspectives. Westport: Praeger Publications; 2009. [Google scholar]

- Clark MM, Anderson BG. Culture and aging: An anthropological study of older Americans. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas Publisher; 1967. [Google scholar]

- Teater B, Chonody J. Promoting active aging: Advancing a framework for social work practice with older adults. Fam Soc: J Contemp Soc Serv. 2017; 98: 137-145. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST. Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2002. [Google scholar]

- Murray C, Lopez A. Global comparative assessments in the health sector: Disease burden, expenditures and intervention packages. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1994. [Google scholar]

- Murray C, Lopez A. The global burden of disease. London: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google scholar]

- Malta S, Doyle C. Butler’s three constructs of ageism in Australasian Journal on Ageing. Australas J Ageing. 2016; 35: 232-235. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Davidson WAS. Metaphors of aging in science and the humanities. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1991. [Google scholar]

- Roos V. Intergenerational interaction between institutionalized older persons and biologically unrelated university students. J intergenerational Relationships. 2004; 2: 79-94. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Schumacher KL, Jones PS, Melios AI. Life transitions in the older adult: Issues for nurses and other health professionals. New York: Springer; 1999. [Google scholar]

- Darzins P, Marriott J. Ethical and practical dimensions of prescribing for older people as quality of life decreases. J Pharm Res. 2008; 38: 64-68. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- HelpAge International. Equal treatment, equal rights: Ten actions to end age discrimination. London: HelpAge International; 2001. [Google scholar]

- Holcomb LP, Gieson CR. Variations on a theme: Diversity and the psychology of women. Albany: State University of New York; 1995. [Google scholar]

- Judge L. The rights of older people: International law, human rights mechanisms and the case for normative standards. London: The International Federation on Ageing (IFA); 2009. [Google scholar]

- Johnstone MJ, Kanitsaki O. Ethnic aged discrimination and disparities in health and social care: A question of social justice. Aust J Ageing. 2008: 27: 110-115. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Wirth L. The science of men (women) in the world crisis. New York: Columbia University Press; 1945. [Google scholar]

- De Hennezel M. The warmth of the heart prevents your body from rusting: Ageing without growing old. Melbourne: Scribe Publications Pty Ltd; 2008. [Google scholar]

- Kenyon GM. Emergent theories of aging. New York; Springer; 1988. [Google scholar]

- Jamieson A, Harper S. Critical approaches to ageing in later life. Buckingham: Open University press; 1997. [Google scholar]

- Turner B. Outline of a theory of citizenship. Sociology. 1990; 24: 189-217. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Turner B. The condition of citizenship. London: Sage; 1993. [Google scholar]

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Respect and choice: A human rights approach for ageing and health. Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission; 2012. [Google scholar]

- Carnell K, Paterson R. Review of national aged care quality regulatory processes. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2017. [Google scholar]

- McCarthy B. Hearing the person with dementia. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2011. [Google scholar]

- Kurrie S. Elder abuse. Aust Fam Physician. 2004; 33: 807-812. [Google scholar]

- Kurrie S, Naughton G. An overview of elder abuse and neglect in Australia. J Elder Abuse Neglect. 2008; 20: 108-125. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee M. Caregiver stress and elder abuse among Korean family caregivers of older adults with disabilities. J Fam Violence. 2008; 23: 707-712. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Assembly, UN General. Principles of older persons. General Assembly resolution 46/91; 1991 http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Professionalinterest/Pages/OlderPersons.ashx (cited date: 2012, June 10).

- World Health Organisation. Global age- friendly cities: A guide. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2007; 9789241547307. [Google scholar]

- Parliament of Victoria. Inquiry into environmental design and public health in Victoria. Melbourne: Legislative Council-Environmental and Planning References Committee; 2012; 978-0-9872446-2-8. [Google scholar]

- Nisoli E, Carruba MO. Emerging aspects of pharmacotheraphy for obesity and metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Res. 2004; 50: 453-469. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Clarfield M, Bergman H, Kane R. Fragmentation of care for frail older people – an international problem. Experience from three countries - Israel, Canada, and the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001; 49: 1714-1721. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Dare J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: Implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2004; 59: 255-263. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Clarfield M, Rosenburg E, Brodsky J, Bentur N. Healthy aging around the world: Israel too?. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004; 6: 516-520. [Google scholar]

- Politt PA. Dementia in old age: An anthropological perspective. Psychol Med. 1996; 26: 1061-1074. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Guralink JM. Prospects for the compression of morbidity; The challenge posed by increasing disability in the years prior to death. J Aging Health. 1991; 3: 138-154. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Fries JF. Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. New Engl J Med. 1980; 303: 130-135. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Olshansky SJ, Rudberg MA, Carnes BA, Cassel CK, Brody JA. Trading off longer life for worsening health: The Expansion of Morbidity Hypothesis. J Aging Health. 1991, 3: 194-216. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Heikkinen E. What are the main risk factors for disability in old age and how can disability be prevented? [Internet]. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2003 [cited date (2013, January 20)]. Available from: http://www.euro.int/document/E82970.pdf.

- Brasher K. Discussion paper for NPC- Effective health promotion for older people. Melbourne: Council on the Ageing (Victoria); 2012. [Google scholar]

- Heuser MD, Hazzard WR. Geriatric medicine. JAMA. 1994; 271: 1675-1677. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Disability and ageing Australian population patterns and implications. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW); 2000. [Google scholar]

- Gawande A. Being mortal: Illness, medicine, and what matters in the end. London: Profile Books; 2015. [Google scholar]

- Schroder-Butterfill E, Marianti R. A framework for understanding old age vulnerabilities. Ageing Soc. 2006; 26: 9-35. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Miles A, Elliot J. Person-centeredness in health and social care-what exactly is it that patients and their carers want?. Eur J Pers-Centered Healthc. 2018; 6: 1-4. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Zeilig H. The critical use of narrative and literature in gerontology. Int J Ageing Later Life. 2011; 6: 7-37. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Braathen SH, Munthali A, Grut L. Explanatory models for disability: Perspectives of health providers working in Mulawi. Disabil Soc. 2015; 30: 1382-1396. [CrossRef] [Google scholar]

- Bigby C. Ageing with a lifelong disability: A guide to practice, program and policy issues for human service professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2004. [Google scholar]

- Larsson H, Ramgard M, Bolmsjo I. Older persons’ existential loneliness, as interpreted by their significant others-an interview study. BMC Geriatr. 2017; 17: 138. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Taube E, Jakobsson U, Meldov P, Kristensson J. Being in a bubble: The experience of loneliness among older people. J Adv Nurs. 2016; 72: 631-640. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Gierck M. Take your time to really hear others. The Age. 2018; 30. [Google scholar]

- Burbank PM, Dowling-Castronovo A, Crowther MR, Capezuti EA. Improving knowledge and attitudes toward older adults through innovative educational strategies. J Prof Nurs. 2006; 22: 91-97. [CrossRef] [Google scholar] [PubMed]