A Review of Oral Health in Older Adults: Key to Improving Nutrition and Quality of Life

Ezekiel Ijaopo *![]() , Ruth Ijaopo

, Ruth Ijaopo![]()

- East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust, William Harvey Hospital, Ashford, Kent, United Kingdom

* Correspondence: : Ezekiel Ijaopo ![]()

Academic Editor: Michael Fossel

Received: April 26, 2018 | Accepted: August 16, 2018 | Published: August 27, 2018

OBM Geriatrics 2018, Volume 2, Issue 3 doi:10.21926/obm.geriatr.1803010

Recommended citation: Ijaopo E, Ijaopo R. A Review of Oral Health in Older Adults: Key to Improving Nutrition and Quality of Life. OBM Geriatrics 2018;2(3):010; doi:10.21926/obm.geriatr.1803010.

© 2018 by the authors. This is an open access article distributed under the conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is correctly cited.

Abstract

With increased life expectancy coupled with falling birth rate, issues concerning population ageing have vital outcomes and effects for all aspects of human life particularly as it relates to older people’s health and health care. Among these issues are oral health diseases which present as major public health concerns and constitute significant burden to all regions of the world. FDI World Dental Federation in 2018, states that 90% of the entire world’s population will be afflicted by oral health problems in their lifetime. The impacts of oral diseases on older people and societies due to functional impairments, disability and reduced quality of life are troubling. This review explores the results of computer searches of databases including PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and EMBASE to review the literature that surrounds the relationship of oral health, nutritional status and quality of life in the older adults’ population. It also aims to provide opportunity for increase knowledge and awareness for the medical staffs, carers and families involve in caring for older people, either in their homes or at health institutions.

Keywords

Oral health; malnutrition; older adults; quality of life

1. Background

With increased life expectancy coupled with falling birth rate, by 2050, the population of older people (60 and older) in the world will overshoot the population of young people (15 and below) for the first time in history [1]. In the United States of America, by 2030, one in five of the population is expected to be 65 years or older [2]. Very similarly to USA, the Office for National Statistics (ONS)-UK reports that by 2035, nearly all the 27 European countries are estimated to have more 20% of their populations consist of people aged 65 or older. Germany is projected to be the most aged country with nearly a third (31%) of its population aged 65 years and over, while 23% of UK population is considered to be those aged 65 and over [3].

Evidently, issues concerning population ageing have vital outcomes and effects for all aspects of human life particularly as it relates to older people’s health and health care [1]. Among these issues are oral health diseases which present as major public health concerns and constitute serious burden to all regions of the world [4].

The WHO defines oral health as “a state of being free from mouth and facial pain, oral and throat cancer, oral infection and sores, periodontal (gum) disease, tooth decay, tooth loss, and other diseases and disorders that limit an individual’s capacity in biting, chewing, smiling, speaking, and psychosocial wellbeing” [4]. FDI World Dental Federation in 2018, states that 90% of the entire world’s population will be afflicted by oral health problems in their lifetime [5]. Undoubtedly, the impacts of oral diseases on older people and societies due to functional impairments, disability and reduced quality of life are troubling [6]. While there may have been great improvements in the oral health population of some countries, the greatest global burden of oral diseases persists particularly among the disadvantaged and less-privileged populations in both developed and developing countries [7,8]. The British Dental Association report that in 2020, people aged 65 and older will express a wide range of dependence such that the provision of access to appropriate oral healthcare will continue to be a challenge for the National Health Service [9]. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services also emphasize the importance of oral health in maintaining general health and well-being of the populations [10].

However, issues relating to oral health care of the older people are often overlooked in the wider health consultation [11]. They are usually neglected due to lack of interest simply because the majority of problems affecting oral health are non-life threatening [12]. Little wonder, it is reported that oral health of a person is likely to deteriorate during hospital admission period [13]. In light of the above, it is therefore not surprising that many physicians, particularly those with no specialty training in caring for the elderly people, often fail to recognise that paying attention to oral health care of older adults’ patients play significant role in helping to address malnutrition/nutritional disorders. This claim is supported by a study of hospitalised patients carried out by Sousa et al. which showed that oral health of patients worsened during the period of hospital admission because oral health was rarely assessed and many hospitals have no policies in place for routine oral health care [14]. Encouraging regular oral health hygiene practice help to prevent nutrition problem in older patients, thus, contribute to improving the quality of life of the older adults’ population [15,16,17,18,19].

Suffice it to say that the normal physiological functions which include our ability to speak, the pleasure of eating and the normal control of saliva often taken for granted by most of us can be significantly affected by oral health problems [20]. The oral cavity plays important role in the eating and speaking functions. Eating is necessary for survival, and speaking is essential for satisfactory verbal communication [21]. In the same manner, oral disease may adversely impact the quality of life of an individual and lead to malnutrition [22].

Malnutrition is a major concern among elderly population [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Many studies have already established an association between poor oral health and malnutrition/undernutrition [19,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. According to Lochs et al., malnutrition “is a state of nutrition in which a deficiency or excess (or imbalance) of energy, protein, and other nutrients causes measurable adverse effects on tissue/body form (body shape, size and composition) and function, and clinical outcome” [37].

Also, there is a lot of polypharmacy due to chronic disease in the elderly people, and these people may also suffer from chewing and swallowing problems that negatively affect their nutritional status, thus, putting them at risk of undernutrition or malnutrition [38,39]. This study aims to review the literature to explores the relationship between oral health, nutritional status and quality of life in the older adults’ population.

2. Recommendations and Targets for Oral Health of Older Adults’ Populations

The 60th World Health Assembly in 2007 centred on action plan for promotion and prevention disease through oral health, encourages member states to appraise mechanisms that provide coverage of the population with essential oral health care, and incorporate oral health as part of the reinforced primary health care scheme for chronic noncommunicable diseases. It also promotes the availability of oral health services directed towards disease prevention and health promotion for the poor and disadvantaged populations [40].

In 2017 the British Dental Association (BDA) supplied evidence to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) updating the standard of oral health care for the older people in care home facilities. These novel guidelines advised that older people in any care home facility in the UK should have their oral care needs assessment done on admission; have documentations of oral care needs in their personal care plan; clean their teeth twice a day as well as having routine daily care for their dentures [41]. In its desire to achieve 2020 vision of oral health services for older people, BDA made several recommendations, among which include recognising the needs of oral health of older population; providing free oral health risk assessment for people above 60 years; and advocating for more research to explore more ways of encouraging effective oral self-care by older people [42].

In like manner, the American Dental Association (ADA) provide general and personalised recommendations with lifestyles considerations for maintaining good oral health. The general recommendations include brushing of teeth twice daily with a fluoride toothpaste; encouraging cleaning between teeth (flossing); eating a healthy diet; and attending regular dentist visits [43]. Going further, ADA lifestyle advice for oral health care encourages consumption of fluoridated water, discourages oral piercings, and advocated for smoking and tobacco cessation [44].

The FDI (Federation Dentaire Internationale also known as the World Dental Federation) and WHO in collaboration with International Association for Dental Research (IADR), developed goals for oral health to be achieved by the year 2020. These goals were formulated to promote oral health so as to help reduce oral diseases burden and minimise their impact on health and psychosocial development among the populations at risk. Also, some of their targets include measures to strengthen activities that control and prevent dental caries, reduce functional limitations from oral disease by controlling pain, replacing missing teeth and treating other impairments such as chewing, swallowing and communication problems [45]. In September 2015, World Dental Federation General Assembly adopted policies that recommend that every country’s oral health surveys should include validated oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) measures that will allow proper explanation for the impacts oral diseases are having on people’s daily life; and that OHRQoL analysis coupled with clinical and behavioural factors should be consolidated into the oral health care needs assessments of the populations, in order to ensure a thorough and full-length strategy to planning oral health services [46].

3. Methods

Computer searches of databases including PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and EMBASE were carried out to identify papers in English, published in the last dozen years (from January 2006 to March 2018). A broad search strategy using the following terms were used: “oral health in older adults” “oral health and nutrition in the elderly” “oral health and malnutrition in older adults’ population” “oral health and quality of life in older adults”. There were over 1000 articles retrieved on oral health; however, only a limited number of these articles actually focused on the oral health-related quality of life and malnutrition in older adults. Observational studies, as well as systematic reviews and meta-analyses studies involving oral health-related quality of life and malnutrition risk in older adults, 60 years and over were selected for review. Reference lists of studies were also manually checked for additional publications. The appendix provides the summary of the 16 studies that met the inclusion criteria. Likewise, recommendations from recognised national and international organisations on oral health of older populations were also reviewed. Data synthesis and conclusion from this review came from available evidence obtained from the studies reviewed and the experts’ guidance.

4. Common Oral Health Problems and Risk Factors

Without the oral cavity, eating and speaking functions will be of great challenge. While speaking is essential for satisfactory verbal communication, eating is necessary for survival [21]. A good oral health is dependent on proper nutrition and eating healthier foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables, calcium, vitamin D rich food and dairy products which strengthen the teeth and bones, as well as playing important role in preventing tooth decay. On the other hand, unhealthy diets such as eating excessive sugary food, energy drinks, lemons, candies among others, attract bacteria which produce acidity that causes gum disease, tooth decay and tooth loss [47]. Table 1 below describes the common oral health problems and their associated risk factors.

Table 1 Common oral health problems and risk factors.

5. Indices for Evaluating Oral Health and Nutritional Assessment of Older Adults

Measures taking to assess and ensure good oral health practice and/or the treatment of oral health problems provide comfort and satisfaction which ultimately improve the quality of life of the individual [18]. Several indices in medical and dental practice are frequently utilized for evaluating subjective oral health care satisfaction of individuals [67]. Each of these indices gives unique result which is used as an outcome measure or an indicator of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) and satisfaction in the person. Table 2A below shows the list of the tools for oral health assessment and brief descriptions are provided for the two most commonly used tools.

Table 2A Tools for evaluating oral health assessment and quality of life.

On the other hand, assessing the nutritional intake of an individual is best carried out by a dietitian [68]. The screening tools for nutritional assessment vary and may include a variety of biochemical markers (haemoglobin, haematocrit, albumin, transferrin, vitamins, folate, and micro-elements levels); anthropometric measurements [weight, height, mid-arm and calf circumference, body mass index (BMI)], nutrition focused physical findings, food and nutrient intake data and other relevant medical and social history [69,70]. Table 2B below shows the commonly used tools and components of nutritional assessment.

Table 2B Indices for evaluating nutritional assessment in older adults.

6. Quality of Life Burdens in Older Adults with Oral Health Problems

Because many older adults suffer from chronic conditions that impair ability to carry out routine daily activities, their oral hygiene and general wellbeing may be compromised, thereby, putting them at higher risk for developing oral health problems [80]. Considerably, any significant infringement on the general health, well-being, and psychosocial behaviour of the elderly people may adversely affect their quality of life [18].

Wu et al. used Geriatrics Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) and Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA) instruments to assess OHRQoL and nutritional status of 195 community-dwelling older people above 65 years in Hong Kong. Their findings showed that 60% of the participants reported undesirable impact of oral health on their quality of life. Likewise, 30% of the participants were found to be malnourished or at risk of malnutrition [19]. Dhama et al. also conducted a cross-sectional study involving 340 participants above 60 years, using GOHAI and OIDPs (Oral Impact on Daily Living) assessment indices to evaluate the impact of oral health on the quality of life and daily performance of community-dwelling older population group in India. The study established the validity and reliability of both OIDP and GOHAI indices as effective measurements of OHRQoL. Dhama et al. demonstrated that the impacts of oral health alter the quality of life of older people particularly, disturbing the physiological functions of chewing, swallowing, and speaking [81].

Generally, the deleterious effects of oral health conditions on the quality of life of older adults may add to the burden of age-related cognitive decline [82]. On the other hand, good oral health defined by the absence of disease, pain or discomfort together with the ability to chew and swallow normally, is very paramount for older people’s dignity [56]. At the same time, subjective satisfaction with diet facilitates good health-related quality of life [21].

Quite pitifully, oral health problems among the older adults’ population also negatively affect quality of life and reduce life expectancy [83,84]. The report of a baseline survey with nearly 4-year follow-up period of 2,011 Japanese community-dwelling elderly individuals to evaluate whether poor oral status can predict future physical frailty pointed out that aggregated oral health problems over a period of time clearly increases the possibility of developing unfavourable health outcomes, physical frailty, and mortality [85]. Also, Brennan and Singh analysis of responses from 444 older adults, to examine the relationships between self-rated oral health and general health showed that 72.2% of the participants that reported poor/fair general health also reported poor/fair oral health. Correspondingly, 61.5% of people that reported good general health also reported good oral health. Vice versa, older people with worse self-rating of their general health experience more distress from oral health problems [16]. The analysis demonstrates a directly proportional relationship between self-rated oral health and self-rated general health.

While possible association between oral health problems and frailty in older adults’ population has been previously reported [86], Ramsay et al. conducted another population-based cohort study of older men across 24 British towns to investigate whether oral health measures have any association on causing physical frailty. Their 3-year follow-up study on 1,622 community-dwelling men aged 71 to 92 years showed that occurrence of frailty was significantly higher in the older people who had complete tooth loss and those with more oral health problems [87]. Similarly, in São Paulo, Brazil, another population-based cohort study of 1,374 community-dwelling adults (≥60years) that evaluated the relationship of oral health issues with physical frailty also demonstrated that edentulous people and individuals requiring dental prostheses had higher likelihood of being frail when compared to individuals with 20 or more teeth, independent of their socioeconomic and general health status [88].

Unfortunately, edentulous older adults with impaired dentition and periodontal disease are prone to developing cardiovascular disease [86,88], or other chronic diseases [53,89,90], and may have increased mortality [91,92] due to eating of unhealthy diets low in vitamins, fruits and vegetables. Likewise, a lifestyle of smoking, alcohol abuse or excessive sugar intake among older adults predisposes them to developing oral diseases (such as gum disease, caries and tooth loss) and chronic disease. Contrariwise, individuals with chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disorders, diabetes mellitus, arthritis, hypertension, renal, liver, gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases, have greater tendency of having compromised oral hygiene, tooth loss and periodontal disease [90,93,94]. Holmlund et al. report that people who had less than ten (10) teeth remaining were seven-times at higher risk of death from coronary heart disease than individuals having more than twenty-five (25) teeth remaining [92].

Some studies have also linked oral bacteria emanating from poor oral health status to possible increased association with the development of upper gastrointestinal cancers such as oesophagus, stomach and pancreas [95,96,97]. A prospective cohort study for nearly eight (8) years investigated the association of periodontal disease, tooth loss, and cancer risk in 48 375 male health professionals in USA, aged between 40-75 years. Analyses of the findings showed that after adjusting for known cancer risk factors such as smoking history and dietary factors, participants with history of periodontal disease had increased overall cancer risk when compared to participants with no history of periodontal disease. The commonest cancers reported were colorectal, melanoma, lung, bladder, and advanced prostate [97].

7. Impacts of Oral Health Problems on the Nutritional Status of Older Adults

In the UK, 1.3 million people over 65 years of age have malnutrition. Likewise, 30% of people 65 years or older admitted to hospital in the UK are at risk of malnutrition [98]. A review of 16 articles by Ray et al. to investigate the prevalence of malnutrition across England hospitals and care homes since 1994 demonstrated that malnutrition prevalence in hospitals ranges from 11 to 45% which emphasizes the long-standing problem of malnutrition in UK hospitals and care homes [27]. Surprisingly, less than half (47%) of UK health and care professionals claimed they had adequate knowledge to recognize and treat older people at risk of malnutrition [99]. Ray et al. proposed the needs for further analysis of malnutrition in order to understand its aetiology, so as to make plan and evaluation for appropriate interventions necessary for its prevention and treatment [27].

El Hélou et al. study conducted on 115 elderlies hospitalized at a public hospital in Lebanon claimed 55.6% of subjects requiring oral care were at risk of nutritional deficiency [100]. Similarly, results of another cross-sectional study by Huppertz et al. evaluating the association between oral health-related problems and nutritional status of 3,220 elderly nursing home residents, aged ≥65 in Netherlands found that elderly residents with poor oral health, particularly, poor eating due to (artificial) teeth problems were about twice more likely to be malnourished when compared with elderly residents who had no oral health-related problems [36].

Similarly, a study of 250 institutionalized elderly people by Gil-Montoya et al. that evaluated the association of the oral health impact profile (OHIP) with malnutrition risk found that 36.8% of the participants had malnutrition or malnutrition risk. Elderly people that reported concerns with oral health status were more than three-fold likely to be malnourished or had malnutrition risk [101]. Unfortunately, nutrition problems in older adults can lead to a number of other health problems which may include reduced cognitive function, tiredness and fatigue, and unintentional weight loss which may contribute to progressive decline in health and reduced functional status [24]. A systematic review of studies involving more than 30,000 elderly participants from several countries, using MNA screening found higher prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalized elderly population and in institutionalised elderly people to be 23% and 37% respectively [69]. Malnutrition problem largely results from poor food/nutrients intake, and/or from diseases that lead to increased nutrient loss from the body, reduced food absorption, or the mixture of the problems [98]. Apparently, these problems may result in increased hospital admissions due to anaemia, poor wound healing, or dysfunctional immune system, among other associated problems, hence, potentially leading to increased risk of mortality [24,68].

While trying to investigate the aetiology of malnutrition in the elderly, a multicentre observational study in three emergency departments (ED) in the United States used a random sample of 252 older adults (≥65 years) to identify modifiable risk factors associated with malnutrition. The study demonstrated oral health problems as the commonest risk factor for malnutrition among older adults on admission at ED, accounting for 54.8% (138) of the participants. Other risk factors identified for malnutrition included lack of transportation, depressive symptoms and drugs side-effects, accounting for 22.8%, 19.8% and 15.2% respectively [102]. A similar study by Pereira et al. that investigated the prevalence of malnutrition among 138 older patients (≥65years) who were cognitively intact and non-critically ill, presenting to an ED in the south-eastern United States, found that nearly two in five (38%) of the participants with oral health-related problems suffer from malnutrition [103].

Besides oral health diseases, the commonly associated risk factors for malnutrition are chronic illness, polypharmacy, institutionalization, as well as psychological and social circumstances of the elderly individuals [24,68,104]. Guigoz et al. claim the psychological changes are dependent on the social situations of the elderly, and these may include living alone, immobility, having poor socioeconomic status and/or the long-term effects associated with chronic diseases [105].

Very lately, a systemic review with meta-analysis of 26 studies carried out by Toniazzo et al. to investigate the relationship of nutritional status and oral health in the elderly, as determined by MNA or SGA found that participants who were malnourished or at risk of malnutrition had significantly fewer teeth present compared to subjects with normal nutrition [106]. Obviously, having fewer teeth may impair chewing and swallowing ability, hence, contributing to nutrient deficiencies in older adults. Similarly, the efficiency of chewing capability in older adults is linked to having good dentition status [107].

Older adults with impaired dentition may be susceptible to having decreased intake of dietary foods rich in major sources of vitamins, minerals, fibre and protein [108]. Hence, the decreased nutrients intake results in malnutrition problems [109]. Among south Brazilians, a randomised survey of 471 independent-living older people (≥60years) who had MNA screening to determine whether poor oral health status is related to developing malnutrition / malnutrition risk, established that 26.5% of participants with poor oral status (gingival problems or edentulous with only one or no teeth) were at risk of malnutrition. In fact, 91 (19.3%) more participants also had risk of malnutrition after full MNA was done [31].

Similarly, in 2016, a 5-year follow-up study of 286 community-dwelling Japanese adults (aged 75 years at baseline) by Iwasaki et al. found significant association between impaired dentition and subsequent decline in dietary intake. Iwasaki et al. report that people with impaired dentition (≤5 functional tooth units) showed evidence of significant decline in their food and nutrients intake compared to those with normal dentition, after potential confounders were adjusted [110]. Having impaired dentition and tooth loss affect the ability to chew food, thereby prompting the individuals affected to change their food preference to low calorie-adjusted nutrient [111]. The intake of most vitamin-containing foods, vegetables and fibre are also reduced in edentulous persons due to impaired chewing capability [86,112]. A cross-sectional study of 353 Japanese elderly evaluating the relationship of oral health status with food and nutrient intake showed significantly reduced intake of multiple nutrients in the participants with poorly-fitting dentures or compromised dentition compared to participants with good dentition [87].

It is an established fact that nutrition is very essential to the maintenance of the optimal functioning of the body defense system [113]. Therefore, older adults who are malnourished/undernourished will have impaired immunity and reduced protection from diseases [113]. A study of 612 older population in Thailand by Samnieng et al, analysed the relationship of nutritional assessment with chewing ability and oral health status, and found that older adults with malnutrition had missing teeth and impaired chewing ability, particularly after making adjustment for age and gender [114].

In Germany, a pilot study of 87 elderly residents in four nursing homes by Ziebolz et al. to explore oral health and nutritional status found that 52% of participants were at risk for malnutrition based on the MNA scores. Although, Ziebolz et al. reported malnutrition risk occurred mainly from dementia compared to oral health problems, they claimed the inability to perform oral examination for the residents due to dementia and bedridden might have possibly influenced study outcome [76]. Conversely, Cousson et al. utilized GOHAI and MNA instruments to evaluate the nutritional status and the general oral quality of life in 47 elderly complete-denture wearers, in comparison with a control group of 50 fully-dentate elderly that visited a French hospital over a 4-year period. The results showed that participants with complete dentures had poorer oral health-related quality of life and 21.3% increased risk of malnutrition when compared to fully dentate control group who had zero percent risk of malnutrition [115]. Identical to Cousson et al. study, Rodrigues et al. claimed there was significant association between tooth loss and poor nutritional status in 33 non-institutionalized elderly individuals assessed in Brazil, thereby increasing their susceptibility to developing chronic diseases [116].

Regardless of the study location, evidence from several studies revealed that poor oral status is associated with undesirable OHRQoL [15]. Therefore, taking active measures to address oral health problems and impaired nutrition will help remarkably to reduce the severity or prevalence of frailty in older people, thereby, causing considerable benefits to the individuals and their loved ones [86,89]. Also, older people that demonstrate a high-level sense of coherence, which is the capability of a person to manage psychological stress and remain healthy, manifest robust outlook with good oral health and nutritional status [90].

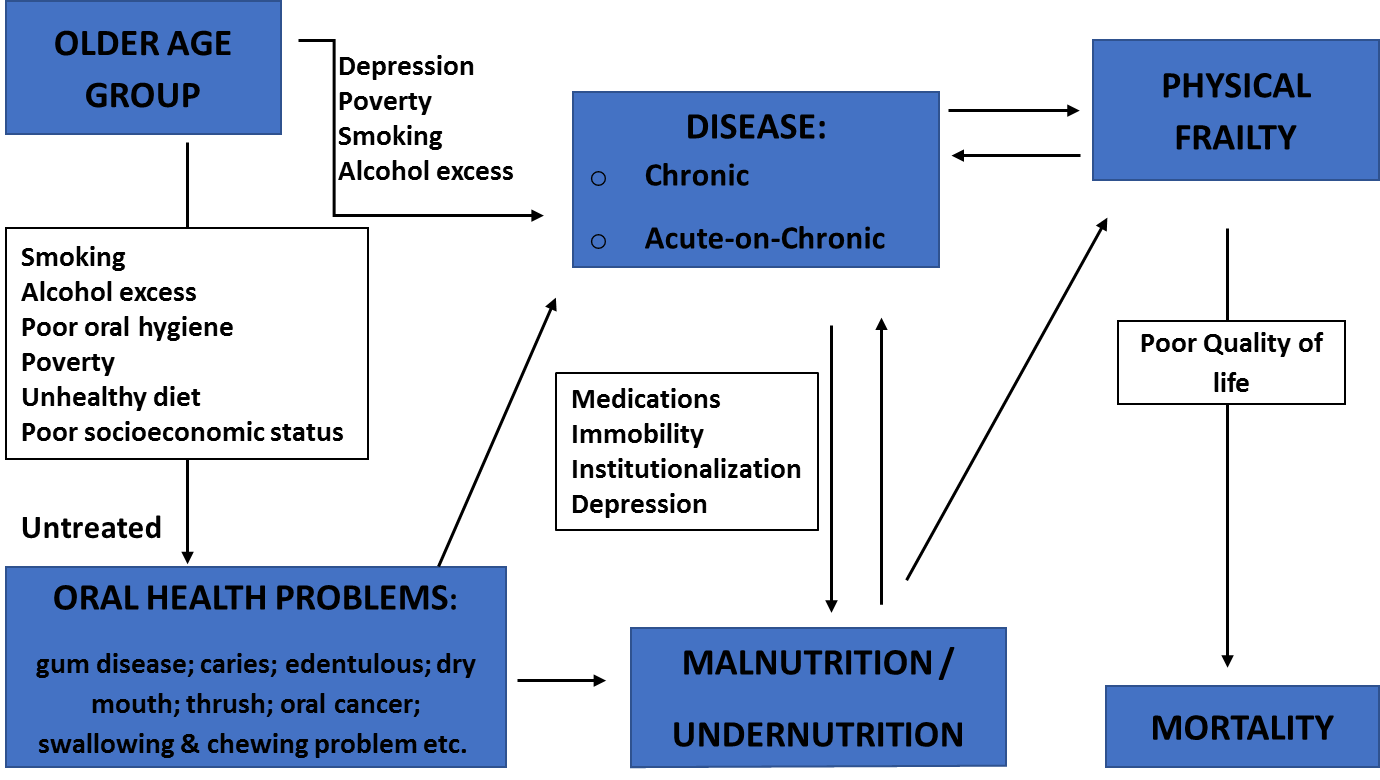

Figure 1 below illustrates the pathways of association between oral health problems, malnutrition and quality of life in the older adults’ population. The flow chart shows that poor lifestyle choices (e.g. unhealthy diet, smoking, excessive alcohol intake, etc) and poor social conditions such as poverty, which have tendencies to predispose older adults to oral health problems and diseases eventually result in nutritional disorders and physical frailty. Correspondingly, individuals with chronic diseases, due to immobility, institutionalisation, depression, or medications adverse effects, are prone to developing nutritional disorders. Unfortunately, both the nutritional disorders and chronic diseases (or acute-on-chronic) lead to physical frailty that plummet the quality of life, and hence, contributing to increased mortality in the older adults’ populations.

Figure 1 Illustrates the pathways of association between oral health problems, malnutrition and quality of life in the older adults’ population.

8. Oral Care in End of Life Care for Terminally-Ill Older Adults

It is important to emphasize at this point that a good oral care is not only beneficial in preventing malnutrition/undernutrition and improving general wellbeing of the elderly population, it is also vital as older people become progressively unwell, nearing end of life [117]. Providing oral care for dying persons helps to promote comfort by relieving dry mouth and reducing the discomfort of terminal dehydration [56]. An exploratory study by Kvalheim et al. assessing the knowledge and practice of oral care in dying patients at 76 Norwegian healthcare institutions (19 hospitals and 57 nursing homes) found that one in four of the responding institutions had no oral care measures, and nearly half (48%) of the institutions failed to recognise the importance of oral care in terminal patients. Kvalheim et al. claimed the most reported explanation cited for providing inefficient palliative oral care for dying patients was due to inadequate knowledge of the healthcare staffs [118]. There is no doubt that families and loved ones of terminally-ill older people will find the latter explanation reprehensible and unacceptable. Oral care of a dying person is a fundamental aspect of end of life care. Patients’ caregivers /relatives should be given proper education and perhaps, be taught to do oral care if they wish, so as to help reduce their distress of not being able to feed their loved one [22,119].

9. Implications for Practice and Recommendations

Effective management of oral health problems will not only help to prevent malnutrition/undernutrition, but pivotal to improving quality of life in the elderly population. Regular oral health hygiene practice (such as regular teeth brushing/cleaning by an individual or carer); carrying out oral health risk assessment; identifying and treating unhealthy oral conditions and recognising abnormal oral changes from age-related changes are essential elements of oral health care [120]. Very importantly, physicians (primary care and hospital doctors) and community nurse specialists should carry out routine nutritional assessment with focused oral examination, and make prompt referrals to dentists, where necessary. Similarly, the involvement of nurses, dieticians, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists, and the social services play significantly roles in oral health care, as well as in the prevention and treatment of malnutrition in the elderly population [24,57].

Annual or periodical dental visit habits should also be encouraged regardless, particularly for the older adults with chronic and debilitating medical conditions so as to make provision for oral health aids, such as electric or customized manual toothbrushes, floss-holding devices, among other things, as may be required.

Since oral health services are important parts of primary geriatric health care [38], comprehensive geriatric assessment also known in some countries as comprehensive older age assessment or geriatric evaluation management and treatment should include nutrition status assessment measures such as MNA [72] and oral health assessment [121].

Also, efforts to control oral disease across all regions of the world should be reinforced through organization of affordable oral health services that meet the needs of older adults’ populations [7]. In addition, older people treated for oral health problems or malnutrition should routinely have follow-up arrangement for nutritional counselling [122].

Available evidence shows that older adults with oral health problems are prone to having unsatisfactory quality of life due to inadequate diet and malnutrition [15,16,17,18,19,68,115,116]. It is therefore, important that nutrition and quality of life assessment process in older adults should involve multidisciplinary team approach, comprising experienced physicians, nurses, dieticians, speech and language team, as well as the individual older adult with or without their family members, as may be required. Full history, physical examinations and necessary laboratory investigations where indicated, should be carried out for each individual [24,37]. In like manner, nutrient deficiencies and poor oral intake due to social, physiological and/or pathological factors should be addressed early, and where appropriate, referrals to psychologists or psychiatrists should be made.

Also, very importantly, physicians and allied health professionals should backtrack from the orthodox belief that oral health care is the sole responsibility of the dental team. They are encouraged to make efforts to join forces with dental team colleagues to diagnose oral health problems in the older adult populations and ensure prompt dental referrals where necessary.

As recommended by Malnutrition Task force in 2018, this review supports the integration of comprehensive oral health module into the training of all health sciences students [99]. A healthy and functioning oral cavity does not only play an essential role in the human digestive system, it is also fundamental and vital for better quality of life and malnutrition prevention among the older adults’ population. Further research including longitudinal studies and controlled trials are needed to establish whether poor oral health increases the risk of malnutrition in the elderly and identify the more vulnerable people among the elderly population.

Acknowledgments

A very special appreciation to Mr John Hudson of Bell library at Royal Wolverhampton NHS Hospital Trust, Wolverhampton UK, for helping with the references. Also, thanks to Mr Joba Odesanya for his help with the flow chart. Finally, to our two kids, Elizabeth and Daniel, we appreciate your invaluable love and supports.

Author Contributions

E. Ijaopo- contributed the following sections: Background; Table for Common Oral Problems and Risk Factors; Quality of Life Burdens in Older Adults with Oral Health Problems; Impacts of Oral Health Problems on the Nutritional Status of Older Adults; Oral Care in End of Life Care for Terminally-ill Older Adults; Implications for Practice and Recommendations; Flow chart; Table showing the Summary of Included Studies.

R. Ijaopo- contributed the following sections: Recommendations and Targets for Oral Health of Older Adults Populations; Table showing Indices for Evaluating Oral Health and Nutritional Assessment in Older People.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- World Population Ageing 2015. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2015 (ST/ESA/SER.A/390).

- Colby S, Ortman J. Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. 2015. US Census Bureau population estimates and projections Retrieved from https://www census gov/content/dam/census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143 pdf. 2016.

- Statistics OfN. Population ageing in the United Kingdom, its constituent countries and the European Union. Office for National Statistics. 2012:1-12.

- WHO. Oral Health: Information sheet: World Health Organization (WHO); 2012 [cited 2018 2018/03/05]. Available from: http://www.who.int/oral_health/publications/factsheet/en/.

- World Oral Health Day: FDI World Dental Federation; 2018 [cited 2018 2018/03/07]. Available from: https://www.fdiworlddental.org/fdi-at-work/world-oral-health-day.

- Petersen P. Oral health. In: Heggenhaugen K, Quah SR, editors. International encyclopedia of public health. Vol. 4. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2008. p. 677-685. [CrossRef]

- Petersen PE, Yamamoto T. Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005; 33: 81-92. [CrossRef]

- Huang DL, Park M. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic oral health disparities among US older adults: oral health quality of life and dentition. J Public Health Dent. 2015; 75: 85-92. [CrossRef]

- Oral Healthcare for Older People 2020 Vision. A BDA Key Issue Policy Paper. London: British Dental Association, May 2003. Report No.: None.

- Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, 2000. SERVICE USPH; 2008 2008. Report No.: NIH Publication no. 00-4713.

- Broadbent JM, Zeng J, Foster Page LA, Baker SR, Ramrakha S, Thomson WM. Oral Health-related Beliefs, Behaviors, and Outcomes through the Life Course. J Dent Res. 2016; 95: 808-813. [CrossRef]

- Wong ML, Thean HP. Geriatric oral health – appreciating and addressing it with a team approach. In: Stuart R, editor. Oral Health Care Handbook. New York: Orange Apple; 2017. p. 67-76.

- Terezakis E, Needleman I, Kumar N, Moles D, Agudo E. The impact of hospitalization on oral health: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2011; 38: 628-636. [CrossRef]

- Sousa LL, e Silva Filho WL, Mendes RF, Moita Neto JM, Prado Junior RR. Oral health of patients under short hospitalization period: observational study. J Clin Periodontol. 2014; 41: 558-563. [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen AE, Allen PF, Witter DJ, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NH. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010; 8: 126. [CrossRef]

- Brennan DS, Singh KA. General health and oral health self-ratings, and impact of oral problems among older adults. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011; 119: 469-473. [CrossRef]

- Sischo L, Broder HL. Oral health-related quality of life: what, why, how, and future implications. J Dent Res. 2011; 90: 1264-1270. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Montoya JA, de Mello AL, Barrios R, Gonzalez-Moles MA, Bravo M. Oral health in the elderly patient and its impact on general well-being: a nonsystematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2015; 10: 461-467. [CrossRef]

- Wu LL, Cheung KY, Lam PYP, Gao XL. Oral health indicators for risk of malnutrition in elders. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018; 22: 254-261. [CrossRef]

- Griffin SO, Jones JA, Brunson D, Griffin PM, Bailey WD. Burden of oral disease among older adults and implications for public health priorities. Am J Public Health. 2012; 102: 411-418. [CrossRef]

- Miura H, Hara S, Yamasaki K, Usui Y. Relationship between chewing and swallowing functions and health-related quality of life. In: Stuart R, editor. Oral Health Care Handbook. New York: Orange Apple; 2017. p. 13-24.

- Oral care in patients at the end of life. Christchurch NZ: CDHB Hospital Palliative Care Service, 2008 CDHB Policy Report (Not numbered).

- Chen CC, Schilling LS, Lyder CH. A concept analysis of malnutrition in the elderly. J Adv Nurs. 2001; 36: 131-142. [CrossRef]

- Evans C. Malnutrition in the elderly: a multifactorial failure to thrive. Perm J. 2005; 9: 38-41. [CrossRef]

- Hickson M. Malnutrition and ageing. Postgrad Med J. 2006; 82: 2-8. [CrossRef]

- Hagen T. Malnutrition in elderly a major concern, needs attention oregon: Oregon State University Newsroom; 2009 [cited 2018 2018/04/13]. Available from: http://today.oregonstate.edu/archives/2007/jul/malnutrition-elderly-major-concern-needs-attention.

- Ray S, Laur C, Golubic R. Malnutrition in healthcare institutions: a review of the prevalence of under-nutrition in hospitals and care homes since 1994 in England. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2014; 33: 829-835. [CrossRef]

- Avelino-Silva TJ, Jaluul O. Malnutrition in hospitalized older patients: management strategies to improve patient care and clinical outcomes. INT J Gerontol. 2017; 11: 56-61. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Nutrition for older persons: World Health Organization (WHO); 2018 [cited 2018 2018/04/09]. Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/ageing/en/index1.html.

- Mojon P, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Rapin CH. Relationship between oral health and nutrition in very old people. Age Ageing. 1999; 28: 463-468. [CrossRef]

- De Marchi RJ, Hugo FN, Hilgert JB, Padilha DM. Association between oral health status and nutritional status in south Brazilian independent-living older people. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif). 2008; 24: 546-553. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Montoya JA, Subira C, Ramon JM, Gonzalez-Moles MA. Oral health-related quality of life and nutritional status. J Public Health Dent . 2008; 68: 88-93. [CrossRef]

- Van Lancker A, Verhaeghe S, Van Hecke A, Vanderwee K, Goossens J, Beeckman D. The association between malnutrition and oral health status in elderly in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012; 49: 1568-1581. [CrossRef]

- Nazemi L, Skoog I, Karlsson I, Hosseini S, Mohammadi MR, Hosseini M, et al. Malnutrition, prevalence and relation to some risk factors among elderly residents of nursing homes in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2015; 44: 218-227.

- Poisson P, Laffond T, Campos S, Dupuis V, Bourdel-Marchasson I. Relationships between oral health, dysphagia and undernutrition in hospitalised elderly patients. Gerodontology. 2016; 33: 161-168. [CrossRef]

- Huppertz VAL, van der Putten GJ, Halfens RJG, Schols J, de Groot L. Association between malnutrition and oral health in dutch nursing home residents: results of the LPZ Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc . 2017; 18: 948-954. [CrossRef]

- Lochs H, Allison SP, Meier R, Pirlich M, Kondrup J, Schneider S, et al. Introductory to the ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: terminology, definitions and general topics. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2006; 25: 180-186. [CrossRef]

- Yellowitz JA, Schneiderman MT. Elder's oral health crisis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14 Suppl:191-200. [CrossRef]

- Schimmel M, Katsoulis J, Genton L, Muller F. Masticatory function and nutrition in old age. Swiss Dent J. 2015; 125: 449-454.

- WHO. Sixtieth World Health Assembly: Oral health: action plan for promotion and integrated disease prevention, WHA60.17. World Health Organization, 2007.

- BDA. Oral healthcare for older people: BDA support for NICE quality standard for oral health in care homes 2017 London: british dental association; 2018 [cited 2018 2018/03/09]. Available from: https://bda.org/dentists/policy-campaigns/research/patient-care/older-people.

- BDA. Oral healthcare for older people: 2020 vision. A BDA Key Issue Policy Paper. London: British Dental Association, 2003.

- ADA. Oral health topics: aging and dental health USA: American dental association. center for scientific information; 2018. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/aging-and-dental-health.

- ADA. Home Oral Care: Key Points. USA: ADA Science Institute's Center for Scientific Information; 2018.

- Hobdell M, Petersen PE, Clarkson J, Johnson N. Global goals for oral health 2020. Int Dent J. 2003; 53: 285-288. [CrossRef]

- FDI. FDI Policy Statement: Oral Health and Quality of Life. Adopted by the FDI General Assembly: 24 September 2015, Bangkok. Thailand: Federation Dentaire Internationale (FDI), 2015.

- Scardina GA, Messina P. Good Oral Health and Diet. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012; 2012: 720692.

- Heath H. Promoting older people’s oral health harrow: RCN publishing company; 2011. Available from: http://www.wales.nhs.uk/documents/Promoting-older-peoples-oral-health_NursingStandards.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and The Merck Company Foundation. The State of aging and health in America 2007. The merck company foundation. 2007. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/saha_2007.pdf.

- Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla T. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011-2012. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2015.

- CDC. Disparities in Oral Health USA: centers for disease control and prevention; 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/oral_health_disparities/index.htm.

- Albandar JM. Global risk factors and risk indicators for periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000. 2002; 29: 177-206. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Amar S. Periodontal disease and systemic conditions: a bidirectional relationship. Odontology. 2006; 94: 10-21. [CrossRef]

- Eke PI, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Borrell LN, Borgnakke WS, Dye B, et al. Risk indicators for periodontitis in US adults: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2016; 87: 1174-1185. [CrossRef]

- Nazir MA. Prevalence of periodontal disease, its association with systemic diseases and prevention. Int J Health Sci. 2017; 11: 72-80.

- Doshi M. Mouth Care Matters: A guide for hospital healthcare professionals. London: NHS Health Education England, 2016.

- Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005; 83: 661-669.

- Thomson WM. Dry mouth and older people. Aust Dent J. 2015; 60 Suppl 1:54-63. [CrossRef]

- Stein P, Aalboe J. Dental care in the frail older adult: special considerations and recommendations. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2015; 43: 363-368.

- Mortazavi H, Baharvand M, Movahhedian A, Mohammadi M, Khodadoustan A. Xerostomia due to systemic disease: a review of 20 conditions and mechanisms. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014; 4: 503-510. [CrossRef]

- Dhanuthai K, Rojanawatsirivej S, Thosaporn W, Kintarak S, Subarnbhesaj A, Darling M, et al. Oral cancer: a multicenter study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2018; 23: e23-e29.

- Ghantous Y, Abu Elnaaj I. Global Incidence and Risk Factors of Oral Cancer. Harefuah. 2017; 156: 645-649.

- NIH. Oral cancer incidence (New Cases) by age, race, and gender USA: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institutes of Health (NIH); February 2018 [cited 2018 2018/06/04]. Available from: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/oral-cancer/incidence.

- Ram H, Sarkar J, Kumar H, Konwar R, Bhatt ML, Mohammad S. Oral cancer: risk factors and molecular pathogenesis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 10: 132-137. [CrossRef]

- Kumar M, Nanavati R, Modi TG, Dobariya C. Oral cancer: etiology and risk factors: a review. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016; 12: 458-463. [CrossRef]

- Risk Factors for Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Cancers USA: American cancer society; medical and editorial content team; 2018. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/oral-cavity-and-oropharyngeal-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html.

- Bettie NF, Ramachandiran H, Anand V, Sathiamurthy A, Sekaran P. Tools for evaluating oral health and quality of life. J Pharm Bioall Sci. 2015; 7(Suppl 2): S414-S419. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed T, Haboubi N. Assessment and management of nutrition in older people and its importance to health. Clin Interv Aging. 2010; 5: 207-216.

- Guigoz Y. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) review of the literature--What does it tell us? J Nutr Health Aging. 2006; 10: 466-485; discussion 485-467.

- Favaro-Moreira NC, Krausch-Hofmann S, Matthys C, Vereecken C, Vanhauwaert E, Declercq A, et al. Risk factors for malnutrition in older adults: a systematic review of the literature based on longitudinal data. Adv Nutr (Bethesda, Md). 2016; 7: 507-522. [CrossRef]

- Atchison K. The general oral health assessment index. Measuring oral health and quality of life Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. 1997:71-80.

- Slade GD. Measuring oral health and quality of life: Department of Dental Ecology, School of Dentistry, University of North Carolina; 1997.

- Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the oral health impact profile. community dental health. 1994; 11: 3-11.

- Stratton RJ, Hackston A, Longmore D, Dixon R, Price S, Stroud M, et al. Malnutrition in hospital outpatients and inpatients: prevalence, concurrent validity and ease of use of the 'malnutrition universal screening tool' ('MUST') for adults. Br J Nutr. 2004; 92: 799-808. [CrossRef]

- BAPEN. Introducing ‘MUST’ London: British Association for Parental and Enteral and Nutrition (BAPEN); 2016 [cited 2018 2018/03/20]. Available from: http://www.bapen.org.uk/screening-and-must/must/introducing-must.

- Ziebolz D, Werner C, Schmalz G, Nitschke I, Haak R, Mausberg RF, et al. Oral health and nutritional status in nursing home residents-results of an explorative cross-sectional pilot study. BMC Geriatr. 2017; 17: 39. [CrossRef]

- Vellas B, Villars H, Abellan G, Soto ME, Rolland Y, Guigoz Y, et al. Overview of the MNA--Its history and challenges. J Nutr Health Aging. 2006; 10: 456-463.

- Detsky AS, McLaughlin JR, Baker JP, Johnston N, Whittaker S, Mendelson RA, Jeejeebhoy KN. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1987; 11: 8-13. [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj S, Ginoya S, Tandon P, Gohel TD, Guirguis J, Vallabh H, et al. Malnutrition: laboratory markers vs nutritional assessment. Gastroenterol Rep. 2016; 4: 272-280. [CrossRef]

- Moore D, Davies G. What is known about the oral health of older people in england and wales a review of oral health surveys of older people. London: Public Health England, 2015.

- Dhama K, Razdan P, Niraj LK, Ali I, Patthi B, Kundra G. Magnifying the senescence: impact of oral health on quality of life and daily performance in Geriatrics: a cross-sectional study. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2017; 7(Suppl 2): S113-S118. [CrossRef]

- Porter J, Ntouva A, Read A, Murdoch M, Ola D, Tsakos G. The impact of oral health on the quality of life of nursing home residents. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015; 13: 102. [CrossRef]

- Hayasaka K, Tomata Y, Aida J, Watanabe T, Kakizaki M, Tsuji I. Tooth loss and mortality in elderly Japanese adults: effect of oral care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013; 61: 815-820. [CrossRef]

- Iinuma T, Arai Y, Takayama M, Abe Y, Ito T, Kondo Y, et al. Association between maximum occlusal force and 3-year all-cause mortality in community-dwelling elderly people. BMC oral health. 2016; 16: 82. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka T, Takahashi K, Hirano H, Kikutani T, Watanabe Y, Ohara Y, et al. Oral frailty as a risk factor for physical frailty and mortality in community-dwelling elderly. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Torres LH, Tellez M, Hilgert JB, Hugo FN, de Sousa MD, Ismail AI. Frailty, frailty components, and oral health: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015; 63: 2555-2562. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay SE, Papachristou E, Watt RG, Tsakos G, Lennon LT, Papacosta AO, et al. Influence of poor oral health on physical frailty: a population-based cohort study of older British men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018; 66: 473-479. [CrossRef]

- de Andrade FB, Lebrao ML, Santos JL, Duarte YA. Relationship between oral health and frailty in community-dwelling elderly individuals in Brazil. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013; 61: 809-814. [CrossRef]

- Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London, England). 2013; 381: 752-762. [CrossRef]

- Dewake N, Hamasaki T, Sakai R, Yamada S, Nima Y, Tomoe M, et al. Relationships among sense of coherence, oral health status, nutritional status and care need level of older adults according to path analysis. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017; 17: 2083-2088. [CrossRef]

- Krall E, Hayes C, Garcia R. How dentition status and masticatory function affect nutrient intake. J Am Dent Assoc(1939). 1998;129(9):1261-1269. [CrossRef]

- Joshipura KJ, Willett WC, Douglass CW. The impact of edentulousness on food and nutrient intake. J Am Dent Assoc(1939). 1996; 127: 459-467. [CrossRef]

- Hung HC, Colditz G, Joshipura KJ. The association between tooth loss and the self-reported intake of selected CVD-related nutrients and foods among US women. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005; 33: 167-173. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki M, Taylor GW, Manz MC, Yoshihara A, Sato M, Muramatsu K, et al. Oral health status: relationship to nutrient and food intake among 80-year-old Japanese adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2014; 42: 441-450. [CrossRef]

- Oluwagbemigun K, Dietrich T, Pischon N, Bergmann M, Boeing H. Association between Number of Teeth and Chronic Systemic Diseases: A Cohort Study Followed for 13 Years. Plos One. 2015; 10: e0123879. [CrossRef]

- Demmer RT, Molitor JA, Jacobs DR, Jr., Michalowicz BS. Periodontal disease, tooth loss and incident rheumatoid arthritis: results from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and its epidemiological follow-up study. J Clin Periodontol. 2011; 38: 998-1006. [CrossRef]

- Nagpal R, Yamashiro Y, Izumi Y. The two-way association of periodontal infection with systemic disorders: an overview. Mediators Inflamm. 2015; 2015: 793898. [CrossRef]

- BAPEN. Introduction to Malnutrition London: British Association for Parental and Enteral and Nutrition (BAPEN); 2017 [cited 2018 2018/03/20]. Available from: http://www.bapen.org.uk/about-malnutrition/introduction-to-malnutrition?showall=&start=4

- Naidoo S. Oral Health and Nutrition. In: Stuart R, editor. Oral Health Care Handbook. New York: Orange Apple; 2017. p. 131-142.

- Abnet CC, Qiao YL, Dawsey SM, Dong ZW, Taylor PR, Mark SD. Tooth loss is associated with increased risk of total death and death from upper gastrointestinal cancer, heart disease, and stroke in a Chinese population-based cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2005; 34: 467-474. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Montoya JA, Ponce G, Sanchez Lara I, Barrios R, Llodra JC, Bravo M. Association of the oral health impact profile with malnutrition risk in Spanish elders. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013; 57: 398-402. [CrossRef]

- Burks CE, Jones CW, Braz VA, Swor RA, Richmond NL, Hwang KS, et al. Risk Factors for Malnutrition among older adults in the emergency department: a multicenter study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017; 65: 1741-1747. [CrossRef]

- Pereira GF, Bulik CM, Weaver MA, Holland WC, Platts-Mills TF. Malnutrition among cognitively intact, noncritically ill older adults in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2015; 65: 85-91. [CrossRef]

- McMinn J, Steel C, Bowman A. Investigation and management of unintentional weight loss in older adults. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011; 342: d1732. [CrossRef]

- Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: the mini nutritional assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutr Rev. 1996; 54(1 Pt 2): S59-65. [CrossRef]

- Toniazzo MP, Amorim PS, Muniz FW, Weidlich P. Relationship of nutritional status and oral health in elderly: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2017.

- Sierpinska T, Golebiewska M, Dlugosz JW. The relationship between masticatory efficiency and the state of dentition at patients with non rehabilitated partial lost of teeth. Adv Med Sci. 2006; 51 Suppl 1: 196-199.

- Sahyoun NR, Lin CL, Krall E. Nutritional status of the older adult is associated with dentition status. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003; 103: 61-66. [CrossRef]

- Sheiham A, Steele J. Does the condition of the mouth and teeth affect the ability to eat certain foods, nutrient and dietary intake and nutritional status amongst older people? Public Health Nutr. 2001; 4: 797-803. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki M, Yoshihara A, Ogawa H, Sato M, Muramatsu K, Watanabe R, et al. Longitudinal association of dentition status with dietary intake in Japanese adults aged 75 to 80 years. J Oral Rehabil. 2016; 43: 737-744. [CrossRef]

- El Hélou M, Boulos C, Adib SM, Tabbal N. Relationship between oral health and nutritional status in the elderly: a pilot study in Lebanon. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2014; 5: 91-95. [CrossRef]

- Samnieng P, Ueno M, Shinada K, Zaitsu T, Wright FA, Kawaguchi Y. Oral health status and chewing ability is related to mini-nutritional assessment results in an older adult population in Thailand. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2011; 30: 291-304. [CrossRef]

- Malnutrition Task force. Preventing Malnutrition in later life: Malnutrition in the UK factsheet UK: malnutrition task force; 2018 [cited 2018 2018/03/20]. Available from: http://www.malnutritiontaskforce.org.uk/resources/malnutrition-factsheet/.

- Holmlund A, Holm G, Lind L. Number of teeth as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in a cohort of 7,674 subjects followed for 12 years. J Periodontol. 2010; 81: 870-876. [CrossRef]

- Cousson PY, Bessadet M, Nicolas E, Veyrune JL, Lesourd B, Lassauzay C. Nutritional status, dietary intake and oral quality of life in elderly complete denture wearers. Gerodontology. 2012; 29: e685-e692. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues HL, Jr., Scelza MF, Boaventura GT, Custodio SM, Moreira EA, Oliveira Dde L. Relation between oral health and nutritional condition in the elderly. J Appl Oral Sci: revista FOB. 2012; 20: 38-44. [CrossRef]

- Ellershaw J, Ward C. Care of the dying patient: the last hours or days of life. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2003; 326: 30-34. [CrossRef]

- Kvalheim SF, Strand GV, Husebo BS, Marthinussen MC. End-of-life palliative oral care in Norwegian health institutions. An exploratory study. Gerodontology. 2016; 33: 522-529. [CrossRef]

- Hui D, Dev R, Bruera E. The last days of life: symptom burden and impact on nutrition and hydration in cancer patients. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015; 9: 346-354. [CrossRef]

- SDCEP. Oral health assessment and review: dental clinical guidance. Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP); 2012. Available from: http://www.sdcep.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/SDCEP-OHAR-Version-1.0.pdf.

- Marshall EG, Clarke BS, Varatharasan N, Andrew MK. A Long-Term Care-Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (LTC-CGA) tool: improving care for frail older adults? Can Geriatr J. 2015; 18: 2-10. [CrossRef]

- Bradbury J, Thomason JM, Jepson NJ, Walls AW, Allen PF, Moynihan PJ. Nutrition counseling increases fruit and vegetable intake in the edentulous. J Dent Res. 2006; 85: 463-468. [CrossRef]